...

No words, indeed, for Germany’s stance concerning the horrific scenes coming out of Gaza for an unimaginable seven months now. Seven months. It boggles the mind. Germany has run the full gamut from absurdities like “clap-gate” to actually multiplying arms exports to Israel ten-fold since October 2023, supplying 30% of Israel’s arms.

Here’s a brief snippet of the full hammer of German authoritarianism we’ve been experiencing: Berlin teachers have received a 40-page document on what they’re allowed to say and what not (the 1948 ethnic cleanings of Palestinians by Israel is a myth, for example); journalists, sportspeople, anyone remotely public is getting fired who even so much as posts a wish for a ceasefire on social media; prize-winning Palestinian authors are disinvited from the world’s biggest bookfair in Frankfurt; the police stomps out a handful of candles placed on the street in memory of the now 33.000 confirmed murders in Gaza and the rest of Palestine (plus thousands decomposing under the rubble); a bank has frozen the account of the German branch of the international organisation Jewish Voices for Just Peace in the Middle East, demanding to see a list of members – remember that other time in Germany where the assets of Jews were withheld? Meanwhile, the same bank performs its regular banking duties for the far-right populist party Alternative for Germany, and Die Heimat (the heir of the anti-constitutional fascist party NPD, heir of the Third Reich Nazi party NSDAP).

Apparently, it’s unthinkable that Jewish people around the world can refuse to have this slaughter ongoing in their name and supposed interest. Germany is (yet again) on the wrong side of history, misusing the lives and livelihoods of Palestinians and Israelis who both live in constant fear and conflict, heaping blood on their souls in endless cycles of killing. And why? Because Germany has actually failed processing its past. Rather than blind allegiance to its former enemy, an actual dealing with its atrocious Nazi past would mean defending human rights anywhere now, regardless whose they are, and who broke them. Germany’s arrogance and supremacy reveal themselves yet again in its sole claim to interpret the past, and to project its self-referential conclusions into the present, into the Middle East, disbelieving the opinions and desires of people who are actually concerned.

¶

Yet, the genocide in Gaza glaringly exposes more deeply entrenched issues than a refusal to fully face the past: Western colonialism, racism, and Islamophobia fuel the slaughter in Palestine, and have always done so ever since the first Zionist settlement projects in the middle of the nineteenth century. It is really quite simple: brown babies don’t matter. Arabs don’t. Muslims don’t. Definitely not as much as white Ukranian refugees welcomed with open arms.

As German, I have been utterly enraged by both politicians and people of what is supposed to be “my” country. The lack of empathy and the lack of mobilisation among the people is stunning and unforgivable. I have been to more protests than I care to remember. I have seen the German police in full riot gear batter people, kick, push, pull, and arrest, and those were peaceful sit-ins and authorized demonstrations. I was there. I saw it.

I have also seen the same protesters over and over again for months now, every single week-end. The majority is not European-looking. I am also Iranian. We Middle Easteners are on the street, asking the West to consider us humans, too, with unalienable rights. Where are all the Germans??? Yes, the triple question mark is intentional.

If we didn’t know how the Nazi oppression-machine could happen to our great-grand-parents, now we do: sustained othering of a group of people like Middle Easteners, especially men, their dehumanisation; punishing and preventing dissent and discussion; aggressive police presence and interventions; and most damningly of all the silence of your neighbour. My neighbour. My friends. Just last week-end, I faced deafening silence from people I thought were long-time friends when I told them about my experiences at demonstrations, my fear over an imminent attack on Iran. Not a single word. My friends said…nothing.

And so, we who are outraged also have no words.

Our posters are empty.

That’s not quite true. We have something. Something more than words. Something more than text. You guessed it.

We have punctuation.

Punctuation belongs to the stuff of text, but it isn’t words. At first glance, this might make it mean less, but it actually allows it to mean more. A dot or a dash is not bound to all the highly personal and hence unpredictable associations people have with a particular word and its connotations. Signs are not prey to the ambiguity of translation, and culture-specific terms opening vast hinterlands of social significance. Punctuation is just that, itself. It has no past, and hence no burden, no tricks, no traps for us to stumble into. It can just rest there, on the white page, the blank screen, and exert its force. Just like that.

We all know what “…” means. It means failure. It means being at loss for words. It means the heart’s suffering and the offense sustained to mind is so gigantic that it obliterates any possibility to distil the experience into words. Language disintegrates at so great a hurt to Nature. Yet, we must express, or else –

So, we reach for punctuation.

Dot dot dot is as universal as most marks of punctuation have become in their 2000plus year history (7000 if we count horizontal strokes between paragraphs as punctuation – punctuation walks step-by-step with the development of writing itself). Dot dot dot, also known as points of suspense, also known as ellipsis (the triplet understood as one mark) indicates failed speech, breaking off for immensity of emotion or for creating intrigue and speculation; it can signal unpreparedness or madness, outrage or thoughtfulness; it also holds space for omitted words, drawing attention to the fragmentary nature of a text. It’s curious to ponder how a mark of punctuation confessing to a failure or fragment of writing leapt into being during a time that saw an explosion of written words positively flooding into every corner of Europe and beyond. There is a reason. Here’s why.

Writing – that most accomplished magical outlandish of human inventions, far more impactful than the internet is or ever will be – writing takes time. Took time to develop. And it’s been a communal effort, featuring an enlightened individual or a collective of writers who saw a need for change, and stepped into the breach, offering solutions. What stroke of genius did it take to come up with abstract patterns of incisions in soft moist clay, each representing a sound which, when marshalled together, makes a word (that’s cuneiform for you! From the Middle East, just sayin’.). That’s quite incredible. Capturing speech, and preserving something so ineffable. Making speech visible. Introducing other abstract symbols to orchestrate its rhythms, for example. That’s one of punctuation’s key tasks. The ellipsis joins the line of this age-old impulse to pin a speech phenomenon down onto paper. Interruption.

Rhetoricians in ancient Greece and Rome knew about the effectiveness of stylised interruption. They understood that breaking off mid-sentence is a sign of overwhelming emotions (of anger, love, doubt), an effective tool to persuade listeners or readers of the genuineness of feelings the orator purported to have. Language was all about eloquence and manipulation – and it still is. In a bad way, but also in a good way. Great rhetoricians like Cicero and Quintilian included conscious interruption in their style manuals as an actual tool for persuasion, employed with deliberate precision. They called it aposiopesis, meaning something like “becoming silent”. This rhetorical figure had no symbol yet. Remember, LATINCAMEALONGWITHOUTMUCHPUNCTUATIONORSPACESBETWEENWORDSLETALONEDOTDOTDOTS. Yet, students of style would be able to identify it, and would employ it for effect. Coupled to interruption or aposiopesis was ellipsis, the figure of omission, indicating lapses of some kind. Don’t be confused about your confusion here! It’s meant to be.

Fast forward 1500 years and the orator, impacting and guiding people with his words, is again the ideal man any schoolboy strives to be. The Renaissance rocked book margins like no other epoch, encouraging readers to take profuse notes in the margins, and enabling writers to have conversations with future readers through marginal comments. Often, writers and printers would point out delectable rhetorical figures, allowing readers to not only enjoy the mastery of the literature, but also study how they work by example with the purpose of imitation. And so with aposiopesis.

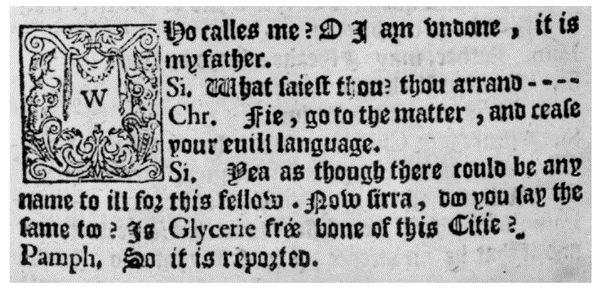

The picture above shows one of the three examples of interruption in the classical play Andria by Roman dramatist Terence. Forbidden trysts, unwanted pregnancies, controlling parents, and clever servants abound, all trademark ingredients of Latin comedy. In this example, Simo catches his son at his lover’s house although he is supposed to marry Chremes’s daughter.

[… ] S. quid ais omnium. C ah:

Rem potius ipsam dic:ac mitte male loqui.

“S, What are you saying of all. C. ah

Come, say what’s up, and stop talking badly.

(This is my bad translation, don’t shoot me!)

Note the lack of “?” after the question ‘quid ais’, but the addition of a full stop after ‘omnium’. The marginal note makes it clear that this is no mistake. Speech cuts off here, ‘ah’ interrupts. It’s an aposiopesis, so we Latin-learners don’t even need to comb the text for any syntactical completion.

¶

The first English translation of the play was in 1520 (which is very early! that’s how much of a staple schoolboy food it was), but there was no punctuation at the end of the line to indicate anything. In 1588, the second English translation appeared by Welsh writer and soldier Morris Kyffin, and here, ladies and gentlemen, comes the first printed ellipsis. Dot Dot Dot. Well, not quite yet. Let me explain!

On three separate occasions, a line of three or four hyphens signals an interruption or broken-off speech, sometimes by someone else, sometimes by the speaker themselves.

This is not by chance. The printer seems to have been careful with the number and placing of hyphens. It wasn’t just a slap-dash job, or chance, or fluke. This was a deliberate making visible of a rhetorical figure through punctuation. Re-using an existing sign, the hyphen that usually connects two words, in a new way in order to signal silence, the impossibility of speech to express a variety of emotions from fear to anger to surprise or shock or joy, creating suspense with this chain of horizontal strokes — that is indeed a quantum leap of writing!

¶

But this was not the first time a Renaissance man reached for punctuation to render a graphic representation of tone, speech rhythms, or the movement of the mind. Apart from the ! for emphasis and feeling, suggested by poet Alpoleio da Urbisaglia in the 1350s, the lawyer and brilliant rhetorician Coluccio Salutati invented parentheses, adding the little typographical walls by hand into a 1399 manuscript he had dictated to his secretary. He sectioned off matter that was not part of the main sentence or argument through parentheses, making visible the ancient rhetorical device of insertion. That’s precisely the same mechanism that also gave us points of suspense or dot dot dot.

Punctuation guru Malcolm Parkes contends that Renaissance writers wished for more nuanced pausing, and hence invented a whole host of marks, including parentheses, the semicolon, the points of suspense, and the dash. I agree, and I would add that they were onto a kind of exploration of the movement of the mind, and how to trace that on paper but not through words. Through punctuation marks. A parenthesis shows our minds having an after-thought, and taking a little detour to include off-path stuff while also returning to the main matter. A bit like offering a safe little space for day-dreaming or mind-wandering.

The dot dot dot is similar in that it gives evidence of our thoughts trailing off…for whatever reason…we might not know what to say, or want to say what’s on the tip or our tongues, or we are overwhelmed by emotion, forget what we want to say, cast around for words. I for one think we think in semicolons; just sort of drifting from one kind-of-sentence to another; it’s all just a stream-of-consciousness; the full stop seems too severe and final, but the comma too rushed.

So, yes, I believe writers and thinkers in the Renaissance were hugely curious about the mind, how it worked, and how one could trace that on the page.

BUT I can hear you exclaim. What is it now? Hyphen-links, or dots, at the centre of the line or bottom or what?

The ellipsis was, in fact, hyphens for another good 200 years in Britain. Let’s follow the vagaries of --- a bit: in the next Andria translation, published in 1627 by Thomas Newman, there are now 29 ellipsis instances. So, that means people had definitely started to understand what it means, and how to use it. Its connection to speaking and thus drama cemented itself, and it makes sense, because such interruption becomes an interactive stage-direction. The reader can see at first glance that the scene is a busy back-and-forth of taking turns between characters, or a particularly dense psychological passage if a character is talking to themselves. Teacher John Bartone calls the points of suspense the ‘eclipsis’ which ‘are noted thus ---‘, adding that they are a common feature of playbooks. Very April 2024! 🌘🌖🌕🌔🌒🌑

And here’s the development we’ve all been waiting for: while the first marking of an interruption or omission through punctuation occurred in Britain by Morris Kyffin, the French were the first to swap hyphens for dots, lowering them to trailing off at the bottom of the line by the 1630s. Around the beginning of the eighteenth century, there is a fair number of English playtexts using the Continental dot dot dot rather than the native hyphen hyphen hyphen. By the end of the century, the dots had won. It’s not clear why, but my guess is that people needed to differentiate between the dash, much en-vogue.

That’s the story of dot dot dot. Some honourable mentions must be made, however! --- one stroke or several often replaced a word, often in an expletive such as “by -----” as early as the seventeenth century. Much mirth ensued one hundred years later when satirists would replace every second word with such hyphenated tipp-ex lines, mocking supposedly true stories about Lord ----- from ----shire who seduced the daughter of Lady ------, Countess of -----don.

Then there’s poor King Lear who breaks off mid-threat, undermining his own posturing:

(Act 2, scene 2)

And then of course, there’s the ominous dot dot dots of modern texting, the typing awareness indicator, exerting such tyrannical influence over modern dating (why are they writing so much? Are we in trouble? Why have they been writing but didn’t send the message???) – but that’s a post for another day…

P.S. Most of this is from the three-times wonderful book Ellipsis in English Literature by the formidably intelligent academic and stylish writer Anne Toner (who, incidentally, taught me Alexander Pope for a few happy hours in a little cosy office at Trinity College, Cambridge). Shout out to the unforeseeable impact of teachers!