Nothing in the world needs to be the way it is – unless we’re talking physical laws of the universe. And even those can be defied if one tries hard enough. It’s not predetermination to work for 40 hours on 5 days a week. If we want it, we can change it. It’s not predetermination that people live in small expensive boxes on top of each other, utterly disconnected. If we want it, we can change it. Palestine can be free — if we want it so.

The recently announced formal recognition of an independent Palestinian State by Norway, Spain, and Ireland (joining the 70% of countries in the UN which already recognise it) is a step towards strengthening that aim although it is a double-edged one: which borders would it have? Would they be of one piece or, like now, scattered and interrupted by Israeli encroachment and legislation? And why should there be two states in the first place? Why should forcibly expelled and internally displaced natives accept the claims of the occupier who has been making facts on the ground through brute force and foreign support for more than 150 years? It does not need to be this way. We can resist. Punctuation does.

In April this year, a very concerned user (irony alert) notified the world on X formerly Twitter that the predictive emoji function on her iphone suggested the Palestinian flag 🇵🇸when she typed the word “Jerusalem” in a text message.

Furious, she added that the software does not propose a national flag upon writing any other capital. Jerusalem is, of course, the hottest bone of contention between Zionist settler-colonialists and Palestinian indigenous: after Israel’s self-declaration in 1948 and the subsequent war with its Arab neighbours, Jerusalem was partitioned but when Israel won the Six Day War in 1967, it captured the city, and now occupies its Eastern Palestinian part, stealing houses, terrorising people, and regularly storming al-Aqsa mosque, one of the holiest sites of Islam. Apple duly apologised for this supposed bug in its recently updated iOS17.4.1 version, promising to fix it, which it has in a matter of days. How did this delicious faux-pas come about? Well, it’s possible that Apple’s machine-learning technology analysed millions of texts from its users who, perhaps, have been adding a 🇵🇸 to the word “Jerusalem”, and so AI made its assumption. It’s also entirely possible, however, that a developer or two at Apple had a point to make, since the prediction software has nothing to offer with any other city. What do you think?

The Palestine flag emoji 🇵🇸 joined the venerable emoji ranks in 2015, and that’s a good thing, because the Unicode Consortium imposed a flag-stop (sorry, Québec!). The Consortium is the mysterious tech body controlling international text encoding in not-exactly-transparent ways. It currently manages 161 scripts from Latin to Aramaic, and synchronises non-alphabetical symbols like punctuation and emojis across mobile operating systems like Android and Apple.

The Consortium also chooses the introduction of the annual set of new emoji additions, and let me tell you, it’s picky! Yours truly is currently attempting an emoji submission (watch this space!), and it’s a rigorous process of persuading the Consortium members of your candidate. During the application process, I caught myself wondering…are emojis punctuation? Sort of. Are they pictures? For sure. Are they writing? Hum, not really. But they are adjacent to letters, accompanying them like a sweet dessert a heavy quiche. Are they a language? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

So, here’s a potted think-piece on the ontology of emojis. That’s a big word for the simple question of: what, in fact, are emojis?

There are currently 3.782 emojis at our disposal. That’s a lot. No wonder the Unicode Consortium doesn’t want to accept just any old proposal. Also, presumably, because once an emoji has made it into the hallowed digital halls of texting, nobody can kick it out anymore. Rules and regulations have changed over the years: at the moment, a new emoji has to argue its right to exist by, for example, avoiding the narrow and instead surfing the broadly applicable wave into different situations we might like to utter. So, no chihuahua dog breed emoji! Too specific.

If you can feasibly glue together an emoji sequence to get to what you want to say, there’s no need for an addition to the already-over-crowded gallery, according to Unicode. Let’s say you watched the amazingly smart classic (yes, it is!) Legally Blonde, and wanted to add a Bruiser Woods chihuahua to your text message, you could for instance bunch together 🐶🇲🇽🎀🐾💅🏻👱🏻♀️.

Yes, granted, it would be faster to just stick a chihuahua emoji in there, but distinctly less fun, and anyway, there are so many options other than emojis at our disposal now to append our words with a visual comment like personalised stickers and gifs on just about any (un)thinkable topic, so we might not need one in the first place. What I find fascinating about the Consortium’s reason for exclusion, though, is the quintessentially figurative mechanism which it asks us to perform. Emojis are all about interpretation. I’m thinking more about that below, because that’s actually a really really difficult task our brains perform.

¶

Emojis & Inclusion

So, there are nearly 4.000 emojis, but it doesn’t mean it’s 4.000 different ones. All the faces and body-parts, for one, are available in 5 different skin-tones plus a Simpsons-yellow since 2015. The same year also saw the introduction of couples and families across the spectrum of sexualities, followed by emoji-people with disabilities in 2019. 👨❤️👨👩👩👧👦 ✊🏽👩🏿🦼Educators find this digital diversity useful for sparking discussion about inclusion; black and brown folks, queer, and disabled people finally found representation beyond the white (yellow?) default. This plethora of choice can get confusing and busy, and can run counter the supposedly spontaneous impression texting gives off. Then again, who said emojis have to function fast and furious? Deciphering which it is we’re looking at, and interpreting their relationship to the text can take quite some time!

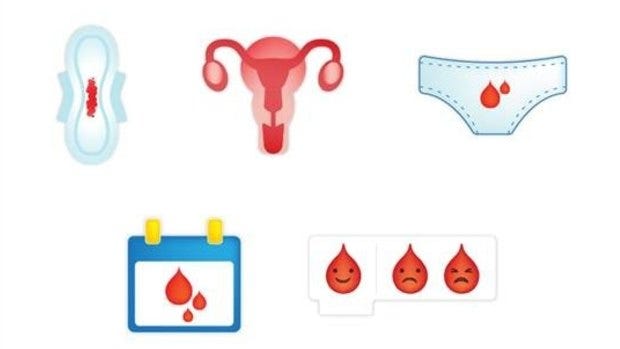

Emojis are powerful communicators, and can provide starting points for conversations across varied social communities. Take the infamous period emoji which, granted, backfired a little, but it was a worthy effort: half of girls and young women up to 34-years of age feel shame around talking about their periods, and believe a period emoji may enable awareness and discussion with their families and environment according to a 2017 survey by the children’s charity Plan International. Over 50.000 people voted on five potential emojis ranging from a blood-drop-trio with faces to a uterus, a calendar, a pad with blood, and period-panties.

Participants picked the bloody panties which reached the Unicode Consortium as proposal in 2018. The mysterious code coven, however, rejected the panties without comment, leading to Plan International banding together with NHS Blood and Transplant in a submission of a noncommittal red drop, de-fusing the specific visual relationship to menstruation into a general blood reference. 🩸It’s unclear to me how an emoji that’s the result of a watered-down version can fight the stigma of period-taboos. It seems that a natural and repeated experience of around 800 million people every day around the world is still too controversial for a group of techies whose squeamish-level ranges between delight at the happy-poop emoji 💩 and shamefaced prudishness over genitalia (eggplant 🍆 and pussy cat anyone? 😺).

I could understand if the reasoning is that the emoji is too particular and only applicable to one context: but the droplet of blood emerged together with over 200 other emojis, among them the waffle, mate tea, a cane and a guide dog. 🧇🧉🦯🦮 A waffle could perhaps…represent Belgium? Brunching? What else? And could we not split a guide dog into a dog and a cane? So, the Consortium’s decision to reject the period panties smacks one as disingenuous at best and misogynistic at worst.

¶

Emoji History

Emojis ruffle our feathers, that’s for sure, but what do period-panties or queer families or hipster drinks have to do with encoding emotion in text? Well, not much. And neither do emojis. A little excursion into the misnomer that’s at the heart of our confusion over our little friends: remember the good old days when we had to pay for each SMS text message rather than shoot off snippets of one-liners like textual machine guns? Remember the days before those even when the first mobile phone bricks trickled into a broader customer-base? The first cell phone I saw was in that Julia Roberts film My Best Friend’s Wedding, and it was *wild*!

Back in the late 1990s when email was a maximum of 250 words, the goal was to say more in less space. A 25-year old designer working for Japanese telecom giant NTT DoCoMo took on the task of developing 176 stylised objects (I’m struggling to find the right label, because, well, it’s kinda hard to say what they are). Shigetaka Kurita offered a mixed bag of pictures for people, places, things, concepts, and feelings in a grid of 12 by 12 pixels. That’s 144 dots, creating the today-classic tile-look we sadly don’t have anymore with our unlimited resolution upscaling. Kurita called his signs emoji, a blend of e for Japanese picture, mo for write, and ji for character as in letter. Perhaps one could translate it as icon or button, or pictograph (a picture conveying meaning through visual resemblance to a real object). No relationship to emotions at all. Emojis’ immediate association to emotions happened when Unicode incorporated them into its system in 2010, starting with 722 items. It makes sense to leap from emo-ji to emo-tion in English. Two years later, and that biggest of addictive Japanese exports conquered communication worldwide.

Then again, emojis are indeed about emotion in so far as we don’t care so much about sending umbrellas or rockets or zodiac signs to each other: we do care about hearts, faces with tears of joy, sad-mouth-faces, thumbs-ups, and prayer-hands 💗😂😔👍🏽🙏🏽. The now-defunct Twitter emoji tracker registered a live evolving ranking of emoji use in all languages, and, to nobody’s surprise, emotion-expressing-faces and body-parts like fingers, and different hearts claim a dynasty of top tiers, untoppled by occasional object emojis. This preference for pictures as ambassadors for facial expression, hand gestures, and (somehow or other) tone of voice emerges time and again in a whole host of studies, so it seems we manage our day-to-day texting with a small set of emotional categories plus (dis)agreement short-cuts like the thumbs-up. Old-school emoticons anyone? :-) :-( ;-)

Humans are social creatures, so how something is being said is as important (or more) as what. In the digital sphere, we’re maximally at a distance from one another, grappling with the lack of presence by sending audio messages, adding stickers, and peppering our texts with emojis padding the cold bare word with a semblance of laughter, warmth, and care. One could argue, as I have (mistakenly?) that emojis might compete with the exclamation mark because both signal to us we need to crank up our emotion-interpretation-muscles for this message. I conceded that they do, in fact, snatch away some of the traditional areas and effects of ! by also coming along as non-alphabetical signs that translate and evoke emotional responses by sender and receiver; and I also assured exclamation mark fans like me that ! will always remain because it’s much more economical than the fiddly faces of emojis which are babies in comparison to “regular” punctuation that’s proved its salt for hundreds if not thousands of years, migrating from material to material – a feat emojis blatantly cannot do, seeing their dependence on computer technology. So, whether 🦄🎉🏝️ will be with us in the future remains to be seen. In any case, though, I now believe that emojis are kind of like punctuation in some ways, but they’re only marginal dwellers in the land of dots and dashes.

¶

So, what are emojis?

Reading and thinking about emojis for a few weeks now has changed my mind somewhat: they certainly partake of the effects of punctuation because we don’t drop them into our messages randomly, but rather at the end of sentences, clauses, or single words even. Nobody would write “thank 🙏🏽 you”, but “thank you 🙏🏽”. Like commas and colons, emojis inhabit a fuzzy mid-way zone between grammatical markers for easier sentence-navigation and infusers of tone or emphasis. But they’re also not like punctuation, because they’re not abstract signs whose concrete meanings or workings we agreed upon. They’re actually things out there in the world, evoking collective and subjectively personal associations.

The interpretive effort upon encountering an emoji is much higher than a punctuation mark: beyond the straightforward faces, we need to contribute our whole life experience to infer the relationship of the picture attached to the words, and this effort grows exponentially if there is a sequence of emojis which all have their individual relationship to the words preceding them, but also relationships among each other.

Emojis seem to have a centrifugal spin, pointing outside of the content of the letters they dovetail. Punctuation, on the other hand, whether it’s actual marks or the bits lingering around the edges like bold or italic or blank paragraphs or ALL CAPS or different typefaces like Calibri and Times New Roman – punctuation is a bit of a navel-gazer; its dynamic is centripetal, drawing us inwards, deeper into the words; encouraging us to ask how the conventions of the punctuation interplay with the text. Punctuation is a process, a verb, a gerund. It’s doing. Emojis are also doing but more…thing-like. They’re things, not verbs, although they can suggest verbs like walking or swimming. I’m still figuring out my thoughts here, bear with me.

¶

Emojis can have a simple comment function, prettifying the message. Let’s say I invite you to a picknick, adding a sun, or food, or a tree emoji or all of them together. 🌞🍓🥨🍬🍌🍅🥯🌳 Because, well, there’s no picknick emoji, so I have to tease out some objects relating to it. But even that mental work on my side (and yours) is quite complex, as they suddenly gain metonymic power: metonymy is a rhetorical device whereby we refer to something not with its own name but a related one. For example, the White House meaning the U.S. president and their government. In the emoji example, there is a picture or a sequence referring to something else that’s connected. This is a lot of brainpower we’re asked to spend!

When I think of digital commenting, I think of #hashtags. You know, that extra little cheeky pizzazz of tone, subverting, self-mocking, commenting, hyperlinking to a whole host of new meanings, so much so that we took it over into our real-life conversations for a while (I remember hearing someone say to me “hashtag awkward”). Yet emojis are not hashtags, although they share the appendix-like after-thought status and outside-directionality.

Are emojis pictures? Yes. And they also have immediate connotations that pictures don’t. Are they “pictographs”? Yes, and at the same time they possess figurative power, rising above the one-to-one traffic of meaning of a pictograph.

Are they ideograms? A symbol representing an idea with or without resemblance to real life whose understanding requires familiarity with convention? Yes. The calendar emoji can refer to just that, a calendar, or to the concept of time. Then again, what about the literal immediate often emotional component of emojis?

Okay, are emojis writing? Well, no, because while they can sometimes replace words, they’re really still functioning through the pictorial.

A language then? That depends what a language is. If it’s a set of elements that may or may not be verbal, functioning together in a systematic way in order to negotiate communication, self-expression, imagination, and social relationships between members of a group – then yes, emojis are a kind of language. If, however, the definition of language requires a somewhat greater level of nuance, flexibility, and range – then emojis are not one, although they partake of some mechanics of language.

Consider, for example, that there are no adverbs or adjectives or even verb emojis. Yes, we have colours and shapes, but if you want to communicate “fast” you’d have to add a car and a cloud or wind 🚙💨, for example, or a person running. 🏃♀️There are, crucially for a language, no verbs. Again, the person running is doing the verb, but it’s not the verb in and of itself. By way of this definition, body language and animal communication possess an ambiguous language status.

I’m sure one could argue either way, but what interests me more than hard and fast categorisation is the process of exploring: journalists and developers like to tout emojis as universal language; as trend-setting transformative peace-ushers of the future, enabling us to overcome the supposed curse of the Tower of Babel. All that pesky diversity of languages! While there’s some truth to this, the reality is much more complex and murky as we’ve seen, heavily inflected by each person’s individual associations, fed by their character, texting familiarity, age, gender, culture, language, extraversion, and intent.

Emojis – just like punctuation, text, spoken words – keep on slithering out of reach, no matter how hard we try to pin them down. In our hungry chase for meaning (and fixing it), we grasp at more and more emojis, more seeming clarity, as we attempt to transfer, selectively, our actual life into virtual space in order to arrange it neatly, finally making sense, finally under control. That is a futile activity, and we might as well catch the wind in a net. We might as well stay with the languages we already have and enjoy their playful waywardness rather than introducing another set of signs whose management adds stress and confusion. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a huge emoji fan and user, and I don’t want to miss them even as I am cognisant of the extra communication ball I’m now required to juggle amid the other balls in the air.

¶

Emojis as social glue.

The most successful attempt to describe emojis I have seen comes from media historian Lisa Gitelman who writes emojis ‘greedily inhabit the tonal register, less as signs with semantic value and more as phatic expressions, communicating the in-commonness of communication’. What she means by this, I think, is that quite what precisely emojis say content-wise isn’t so important; it’s important that there has been an exchange of whatever kind; I see you and you see me; we’re acknowledging one another, we’re spinning a little thread of connection between us; we’ve passed around a kind of emotional coin and/or shook virtual hands. Emojis are the digital equivalent of small talk.

Linguists call small talk “phatic communication”: Polish-British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski coined the term in a 1923 essay, proposing that all the “heys” and “how are yous” and “awful weather, isn’t its” we greet each other with occupy a prominent place in how we relate to one another, operating not as vapid fillers, but as witnesses to our attention, hence respect, honour, and affection. The more trivial the better. Emojis are triviality royals!

Phatic markers like emojis are gestures, translating an attitude, presence, the intention of being sociable. The great writer Anthony Burgess called phatic expressions ‘speech to promote human warmth’. And nowhere do we need that warmth more than in the cold dark disembodied world of texting.

People often ask me about the future of punctuation, and thus of writing. I don’t know. I don’t have a 🔮. Our regular repertoire has stood the test of time pretty well, migrating from medium to medium and textual moment to textual moment. So, I wouldn’t be unduly worried of losing precious punctuation marks, and yet I certainly don’t promote ditching thoughtlessly what humanity has developed over thousands of years.

In many ways, writing is as good as it gets without radical intervention into our biology. On the other hand, design alters behaviour, and design is changing rapidly, and with it our relationship to text and punctuation. Emojis heavily depend on the technology to make them unlike familiar writing and punctuation which we can produce by hand anywhere without the need of a plug and electricity. So, before we enthrone emojis among the ranks of tried-and-tested “stuff” around text, let’s wait and see a little. And while we’re confused where we’re going with writing, we can still ask questions and explore, and enjoy the ride.

Truth be told, I know less about emojis now than I did before. And that is A Good Thing, because it would be shoddy research to dig for evidence for an already-settled answer. I think I understand that emojis share a lot of mechanisms and effects with a lot of other language and text phenomena, and yet they are a species unto themselves. They’re strange. We can marinate in that strangeness and still sprinkle them like confetti into our writing. We don’t have to understand it all before using them. Emojis are likely to morph into something else, and surprise us anyway along the way. You don’t have to be an expert on Middle Eastern history to know and defend that bombing children for eight months is wrong on every possible level. 🆓🇵🇸

Absolutely fascinating, thank you for this! Loved it. 🆓🇵🇸