Two weeks ago, a friend sent me this welcome picture of a righteous prank, and its punctuation-cleansed comment.

Boxes with parts by the German window company Roto Frank arrived at a company in Sha´ar Binyamin in the occupied Westbank with not-so-friendly greetings. This news circled the world, and had the German company make embarrassed apologies, scrambling for investigation how this could have happened. One wonders why Roto Frank is not rather ashamed at delivering material to an industrial park built in 1998 on land stolen from the Palestinian villages of Jaba and Mukhmas, aiding and abetting illegal settlements that violate Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention which, after all, Germany did sign.

As punctuation fan, I was intrigued by the half-hearted attempt to censor or sanitise the F-word in the Tweet of journalist Jack Jackson. Why do we do this? Why do we replace letters with punctuation in semi-transparent attempts to camouflage their meaning? We don´t say the "bad word", but then, we kind of do say it, but not as frankly as the Roto Frank workers (pun intended).

Asterisks and other concealing punctuation is supposed to dissimulate and reveal at the same time. Just enough of both to make the reader get the word, while also preserving perceived language standards or circumventing censorship. Since the start of the genocide in Gaza in October 2023 and the one horrible year of mad authoritarianism that clamps down on free speech which defends human rights, I myself have started to mix up my letters with punctuation to make communication via unsafe media like WhatsApp less readily findable. Because computers are smart, but not that smart if we keep changing our encoding. Surely, you human reader can tell that "fock !sr@hell" means what you think it means. ChatGPT initially struggled with various combinations, but -- and here it gets scary -- it was a fast learner. Very fast.

If it didn´t get "fock" or "f0ck" (with a zero as o) the first time around, it did so at the second try (telling me "fock is likely a shorthand for a profanity"). At first, it suggested that "!sr@hell seems to be a misspelling or stylized version of "sharll" or something similar"; then it said this "could be an attempt to spell "screaming at hell", which had me chuckle, and after the fourth attempt at asking it what the punctuation-dissimulation meant, it got it: "The "f0ck" seems to be a variation of "fuck," and "!sr@hell" might be a play on "Israel" with some letters replaced by symbols."

So, we need to keep on keeping on tricking the system, folks! Why is this important? It is extremly important, because of state surveillance that has very real consequences in Germany where a mere thumbs-up like of a post which the government considers "terrorist" can mean instant deportation to war-zones and execution sentences. Trailing an asylum seeker´s like-history on social media is some serious snooping, so here I am punctuation-replacing the hell out of my letters in text messages to friends, especially to those who are applying for citizenship.

All of this got me thinking...how does this punctuation hide-and-seek work? What´s its history? What does it say about a society that obsesses over its own prudishness while tens of thousands of children are murdered and orphaned, and we´re not even allowed to feel devastated by this never-ending high-tech killing spree? As so often, punctuation is doing some really subtle things for us, fun and smart and mind-jogging -- if we allow it to. Wink, wink: past people were better at this than us. Much better.

WHAT´S BEING HIDDEN, BY WHAT, WHY?

Naughty words. Naughty words hide behind punctuation most of all. Swear words or words considered obscene (like “shit”), slurs (like "faggot"), profanities or religious names used in vain (G-d), allusions to sexy stuff (remember that dot dot dot scene in Mama Mia?), and sensitive information, real or imagined. The latter strategy was particularly common in eigtheenth-century novels on roguish rakes seducing simple maidens: Lord -----ham of -----shire eloped with the daughter of Sir Malcom ——ton of ——— Hills, that sort of thing, so ridiculously over-used that even contemporary works started to satirise this habit of pseudo-mystifying fiction, giving it the titillating veneer of truth.

We have always wanted to cover our letters for different reasons: the asterisk * is the earliest punctuation mark, registering omission since the early Middle Ages. This "little star" originates in Greek-influenced Alexandria where a venerable line of head-librarians worked on making text accessible through punctuation inventions, and that included collecting, preserving, and improving on staple texts of Greek culture like Homer´s epics on the fall of Troy, and the subsequent adventures of wily Odysseus.

Zenodotos of Ephesus, the first librarian, edits these epics, drawing a sort of dagger or spear (called "obelos") into the margin to mark superfluous lines, additions that are not from Homer. Aristarchos of Samothrace, the fourth librarian CEO, introduced our little star for duplicated material and omissions. Here is *, patiently correcting defects for over 2000 years. And we still use them in texting when we misspell a wrd, I mean *word.

Aristarchos, just as an aside, also started putting > (the "dipple") in the margins to flag up something noteworthy. Double that and you´ve got French quotation marks (<<guillemets>>), because when our current punctuation was codified in the Renaissance, people would mark proverbs and poetry lines with quotation marks which, eventually, came to signal "someone else´s speech", whether that be an author or an interlocutor.

Apart from the asterisk hiding letters, there´s also the dash which sprang from the incredible brain of an English playwright towards the end of the sixteenth century, concealing letters at least since the early eigtheenth century. The simple full stop hides full words in their abbreviations or initials (like George W. Bush), and the dot dot dot (also joining around the time of Shakespeare) and etc. or &c. (ancient Roman additions) hint at a continuation that we the readers supply in our heads. The equivalent of wink wink 😉.

We black letters out, or leave a blank space, or - since the Renaissance and its invention of the mighty horizontal stroke - we dash them into oblivion. White space and dashes, in fact, became so common for punctuation-obfuscation that they have seeped into spoken language: "what the dash!" and "blankety blank!" became clean(er) ways of swearing in the nineteenth century.

But you can´t just chuck in an odd * here and a — there. There´s rhyme and reason to our replacements. Consider, for example, the British yellowpress Daily Mail´s report on the most commonly-used swear words in the UK. I´ll let you guess.

1) f***

2) s***

3) bloody

4) p***

5) b****

6) crap

7) c***

8) c***

This is based on an Ofcom ranking, the UK´s Office of Communication, regulating just about everything to do with language, broadcasting, and the media. That´s quite a lot of power.

Replacing all but the initial letter is unhelpful. Is 4 piss or poop? And is cunt before cock, or cock before cunt on places 7 and 8? It matters! That is the thing with punctuation-sanitising, you want the purification to be extensive enough for concealment, yet also restrictive enough to hint at the word in comprehensible ways. We´ll return to this double-bind below. So, most of the time, we replace internal vowels with asterisks or dashes, like sh*t, or we asterisk out the centre like f**k. But we keep grammar intact, so it´s usually f***ing, but not f*c*ing. Often, content-carrying syllables fall prey to the asterisk or dash as in Lady ------ton, not prefixes or suffixes.

Punctuation as placeholders for letters or whole stories are always about hiding — to varying degrees. Sometimes, a word needs to disappear entirely for reasons of security or legal implications; sometimes, a word may trigger offense in readers, and has its sting pulled through stars and dashes; at other times - the best of times - a word rides on both of those all-too-serious motivations: punctuation-ersatz conceals but the meaning of the word shimmers through, paying cheeky lipservice to censorship and playfully teasing those prudish (and foolish) enough to squirm at perceived obscenity. Punctuation-obfuscation can be a playful invitation to participate in this game called reading. Misplaced coyness governs asterisked words in dreary bloodless utilitarian writing like the news. Literature, needless to say, loves the ambiguous effects of punctuation as placeholder for letters. And so do we.

¶

MEDIEVAL MEDDLING, AND, YOU KNOW...

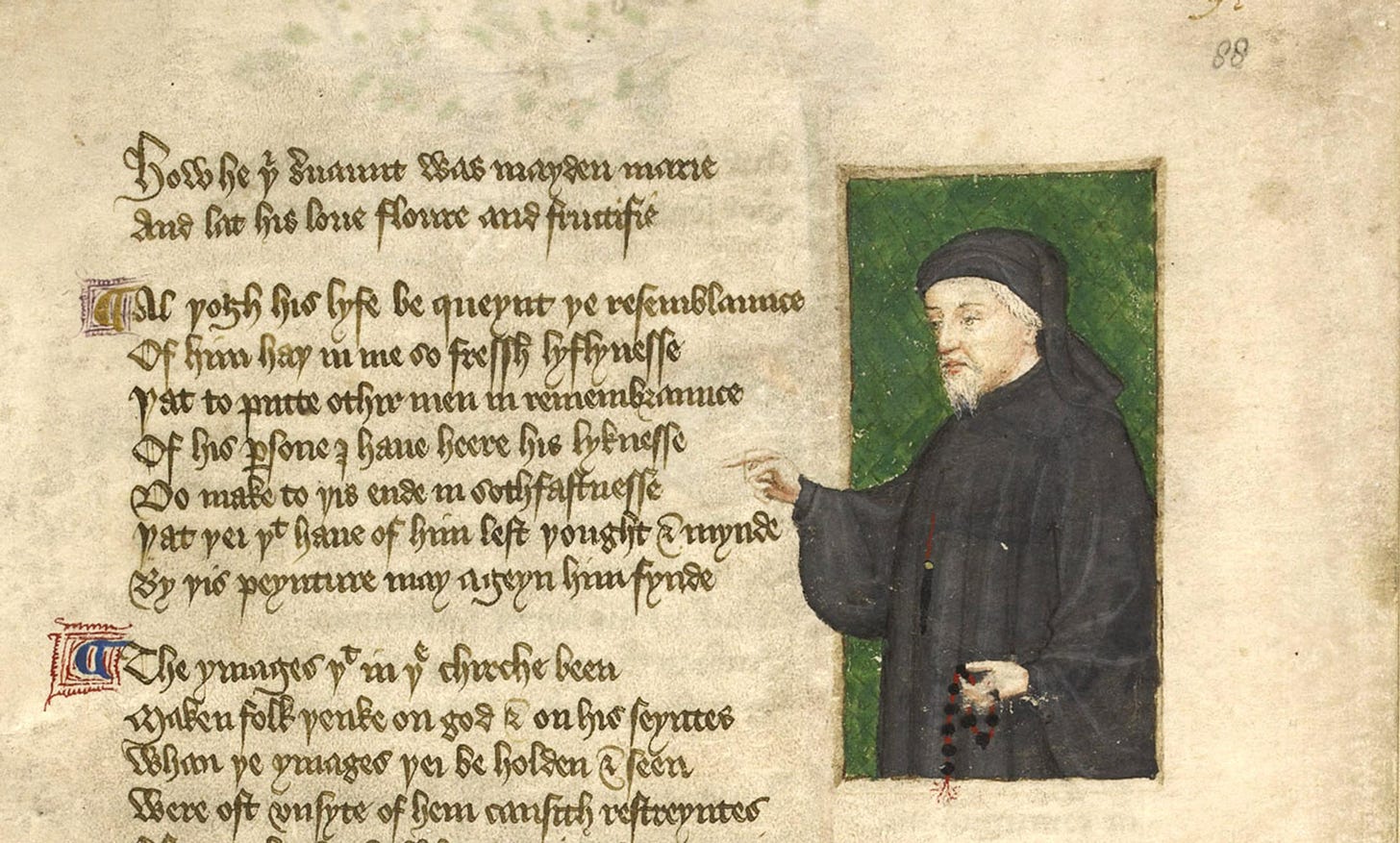

Imagine you´re on a trip with a travel agency, you´re thrown in together with a bunch of people from vastly different backgrounds, and you´re bored during the travelling. Naturally, you chat. You tell stories. Then you start a bet: the person who tells the best story gets invited to a meal by everyone at the end of the journey. Sounds like a fun way to while away the time, right? And so it was for medieval people. Geoffrey Chaucer´s The Canterbury Tales from around 1400 takes this experience as its frame story, having a bunch of pilgrims ride slowly from London to Canterbury, telling each other stories along the way.

Chaucer is a master of wit and gentle humour, and punctuation-play was not foreign to him: the Manciple who is a kind of food manager at a college or monastery recounts how the crow got its black feathers and croaky voice through a curse of the classical god of poetry, Apollo. The god´s white pet crow catches his wife cheating with a lowly dude, and flutters off to his owner to share the news. Mad with hurt and jealousy, Apollo kills both his wife and her lover, then repents and curses the crow with a change of colour and voice. Here´s what the crow whispers to Apollo:

“By god,” said the crow, “I sing not amiss,

Apollo,” said he, “for all your worthiness,

For all your beauty and your gentillesse, (nobility)

For all your song and all your minstralcy,

For all your waiting, bleared is your eye

With one of little reputation,

Not worth to you in comparison

The maintenance of a gnat so may I thrive

For in your bed your wife I sey him &c.”

(Hengwrt Manuscript, fol. 110v, lines 4–12)

Sadly, the online manuscript at the National Library of Wales does not allow either screenshots or saving images, so I can´t include a picture here, but I´d encourage you to have a look for yourself, and pick out the &c here! (Go to the folio page 110v at the lefthand side, zoom in, and find “thryve”.)

I changed the medieval spelling and words somewhat to make the poetry easier to read. The important part are the last two lines: “thryve” in the original rhymes with "swyve", the medieval equivalent of "to fuck". And that´s precisely what we the readers are encouraged to supply here. Chaucer calculates on our minds doing what minds do, which is to leap to what makes sense automatically without our conscious choice, amplifed by the rhyme sounds necessitating the "swyve" inference. It´s that pink elephant paradox: try not to think of a pink elephant now, and you certainly will, because the brain short-circuits choice. Try not to think of the intimated word, and you sure will, whether you´re a chuckling 1400 civil servant or a 2024 New Yorker. Brains will do what brains will do.

There´s also plenty of research on how irresistible rhyming is, boosting memory, increasing pleasure, increasing trust in what´s being rhymed (think of proverbs), and lowering stress (because we need less energy to process the content, so our brain makes us like whatever helps save precious energy). Rhymes make tons of sense to our brain. And Chaucer knew that before we came along, "proving" this knowledge in our fMRI scanners.

Chaucer loves teasing the reader like that: elsewhere in The Canterbury Tales, he shuffles off responsibility to the reader who, if they turn the page, will be reading some saucy stuff. He warned them! It´s up to them to continue or not, and if they do, he can´t be blamed if they become offended by what they´ll read. It´s a bit of a medieval trigger warning, just that it´s not about sparing any feelings, it´s more about a reflection on the act of reading itself: reading is a dynamic interaction between the author and us; we are required to activate our powers of interpretation, questioning, criticising, guessing. It´s not for nothing that "to read" comes from an Old English etymology for "guessing" (and "counselling"!). So, Chaucer is both poking fun at us who think we don´t have dirty minds, and he also places meaning-making squarely on our shoulders: we make The Canterbury Tales happen. It´s a co-creation. The text extends itself beyond the page, beyond time, from Chaucer´s mind to ours, our time, our mind.

Chaucer is not bothered about obscenity. Elsewhere in The Canterbury Tales, there´s plenty of swyving spelled out. In fact, in another manuscript of The Tales, a marginal note even calls out what´s going on with crow and the punctuation, rather than hush-hush it ("nota malum quid" - note something bad). The “&c.” of the crow´s tale works like an asterisk or any attempt to replace words with punctuation: it becomes a magnet for attention, not the other way around. The seventh-century bishop Isidore of Seville wrote how the asterisk "placed next to omissions" makes those very things "shine forth through". Like a twinkling star on a dark night.

Dr Mary Flannery who wrote a fascinating article on this punctuation-game which I´ll reference below suggests Chaucer has the crow break off into &c. as a comment on language: the whole tale is about how to find the right tone, how to say things properly. The mock-coy crow, hiding behind the punctuation, and shriving itself off the weight of words by placing their completion into Apollo´s mind, indeed deserves its feathers to be blackened and its voice to deteriorate into the croak we know. The crow is a little like Chaucer himself, who borrows our minds to finish his meaning. But he knows what he´s doing. The crow hides behind the punctuation, and refuses to accept the weight of words.

Modern editors of The Canterbury Tales, however have all replaced “&c.” with "swyve", assuming the punctuation came about through scribal prudishness. As with most medieval manuscripts, Chaucer´s pages are not actually written by the author himself but copied from authorial papers by his secretary or other scribe, so editors need to decide what to keep and what to change. In book studies, punctuation, sadly, falls under the rubric of so-called "accidentals" of text, that is, it doesn´t have meaning or impact on the text beyond showing personal preference or contemporary conventions. Chaucer´s &c., however, proves this wrong. Punctuation is very much a substantial part of reading and writing and meaning, and it´s not only foolish but also arrogant to dismiss that. We need to make very careful choices when we start meddling. Because it´s us who are uncomfortable with seeing fuck on the page, not people in the past.

¶

Speaking of meddling, another big British author had a thing or two to say about etceteras. In Romeo and Juliet, Romeo´s friend Mercutio tries to tease him regarding his initial crush while he is hiding from his friends after the ball at the Capulets where he forgot all about said crush he sooooo pined over, and secretly fell head-over-heels in love with Juliet. Calling for his friend, Mercutio shouts:

Now will Romeo sit under a medlar tree,

And wish his mistress were that kind of fruit

As maids call medlars when they laugh alone.

O, Romeo, that she were, O that she were

An open etcetera and thou a poppering pear!

Mercutio suggests Romeo imagines himself and his crush as certain sexy fruits such as the medlar (punning on meddling here, that is, having sex) whose age-old common name is “open arse”, because of what it looks like.

Couple this appeareance and popular name to the somewhat phallic-shaped pear from Poperinghe in Belgium (again, playing on "pop her in"), and you have the perfect brew of hilariously evocative allusions. My old lecturer at Cambridge who has edited Romeo and Juliet even proposes Mercutio might be talking about masturbation...

Now, the "open etcetera" stems from the first printing of the play in 1597. The second printing in 1599, and the third both read "an open, or". Modern editors have speculated that the original "etcetera" could be a stage direction, and thus an invitation for the actor to make a rude gesture; it could be faulty diciphering of the manuscript, or the prudishness of typesetters. Really, they believe, Shakespeare wanted to say "open arse" but was either censored or misread, and so this is what editors chose since Hosley´s 1954 edition of the play, reading "open, or" as "ors/arse". I think this is wrong.

It´s possible that the "etcetera" does not refer to an actual piece of punctuation like it did in Chaucer. But it´s also not impossible that it does. In Shakespeare´s time, as it also did afterwards, "etcetera" was a codeword for female genitals, a euphemistic reference to "down there", a kind of Harry Potter-like "You-know-who", or rather "you-know-what". In fact, in the second part of Henry 4, the character Pistol says "are etceteras nothing", playing on Renaissance slang for vaginas (they are "nothings" because there are no things between a woman´s legs, no penises).

So, I think editorial de-coding into explicit choices of what this etcetera might hold a place for is presumptious and restrictive, closing meaning down rather than extending it, running counter the purpose of literary punctuation-play. After all, no editor changes Hamlet´s allusion to "country matters" to"cunt-ry matters". Editorial under-estimation of punctuation as accidental strikes again.

¶

For Part 2, our contemporary obsession with obscenity, tune in again in two weeks! This research went way deeper than I had expected, requiring two parts…until then, feel free to asterisk away at your F-words! Or not. Do as you please!

¶

👉🏽 Mary Flannery, “Et cetera: Obscenity and Textual Play in the Hengwrt Manuscript” in Studies in the Age of Chaucer, Volume 42 (2020), 1-25.