OMG!!!

Why it’s good to speak bad English.

Soooo, do you, like, get totally riled up, like, when someone keeps, like, interrupting themselves with umm and uhh when they’re talkin’, and creakin’ their voice like stupid Paris Hilton or Kim Kardashian or sumfink? Dude, like, that’s mad dumb, WTF!

I think you get where I’m going with this.

Transcribing the way people talk feels strange, stranger than hearing all those supposed verbal “tics” we love to hate. Who hasn’t judged someone upon hearing one like too many? Throw the first stone! I know I have.

What if I told you, then, that what we subjectively see as mannerisms are actually A Good Thing? That they negotiate our social identities and relationships, help us produce speech in the first place, and process what we’re hearing? That they’re a perfectly natural development of language that’s living and breathing, and that there is rhyme and reason to such alleged quirks? That not anything goes?

Linguist Dr Valerie Fridland wrote a whole book about “bad English” called Like, Literally, Dude which I had the pleasure to discuss for the journal Literary Review (November issue). And Reader, it’s a good book! Here’s why we should all umm and uhh a bit more, and what that has to do with punctuation.

Take free-spirited like. Think there’s no rule to where we drop it into the sentence? Think again. While it’s pretty versatile, we wouldn’t perhaps say How like much does this cost? but Like, how much does this cost? or How much does this, like, cost? We tend to put like at the beginning of a sentence, or in front of nouns, verbs, or adjectives, and the purpose is to emphasise the next word. Like helps focus, and so do umm and uhh.

¶

Most speech-giving advice will call such fillers the arch-enemy; that they express uncertainty; uncertainty weakness; weakness losing the discussion. But that is not so. Umm and uhh actually help us come up with what to say, rather than signalling a break-down of speech. We usually place them before new material or more complex syntax. They’re like a gathering of forces for smoother sailing which other fillers such as coughing or just pausing can’t provide.

Apart from assisting the speaker, they also prime the listener to perk up: something new and tricky coming this way! Much like the exclamation mark. (Incidentally, eye-tracking research has shown how commas slightly stall our progress through text as the eye lingers, but then processes the following words faster. One could say umm and uhh are the vocal equivalents of commas, but that’s another post!). So, if you were worried about halting in your speech too much: umm and uhh away!

¶

We tell ourselves (and others) filler words like literally and street language like mate are a sign of lack: lack of intelligence, education, power, money, status, influence, tradition – in short, desirable assets for human beings across time and cultures. And yet again, what we subjectively and consciously believe belies what study after study has found: others perceive us not as less, but more dominant when we use the no-no words. And if we’re not part of the in-group yet, we can establish belonging and dominance by picking up those decried but sneakily mighty ways of talking.

Speakers using intensifiers such as totally, literally, very, completely, and sooooo come across as more confident, convincing, and likeable in linguistic surveys. What about vocal fry? Listen to this if you’re not familiar with the term. You won’t be able to unhear it. Try and imitate it, it’s fun to put on a persona, just like Paris Hilton did herself, as she recently admitted.

Valerie Fridland describes how vocal fry has been around for a few decades without provoking any disgust, yet now we inevitably connect it to the “valley girl” stereotype of a young woman from California with a wealthy family, obsessed with money, status, and personal appearance - a powerful social figure we love to mock. The wonderful Emilia Clarke switches it on nicely! Throwing in a few extra likes and uptalk (see the next paragraph). It turns out, men fry just as much as women, and guess what: the people who publicly fry are all powerful influential figures in pop culture and society at large. So why do we hate it?

Why do we hate “uptalk”? That rising intonation at the end of statements? I’m sure you’ve heard it before? Which we connect to insecure girlies, fishing for agreement? Well, take that misogyny! George Bush jr. was one of the biggest uptalkers! And so are male CEOs and professors in lecture halls according to linguists Winnie Cheng and Martin Warren. Men in the highest echelons of power and prestige. Because rather than suggesting doubt about your abilities, uptalk is a kind of warm hug. If you’re a person who’s got clout anyway, you draw your listeners in, making them feel safer when you lift your voice a bit at the end. It can function as “checking in” if your interlocutor is still listening to you. It can be a part of your local dialect. So, something’s afoot here with us judging certain language habits harshly. And yes, you guessed it: it’s misogyny, racism, classism, and agism. The usual suspects.

Add insult to injury, because women, teenagers, and marginalised groups are the ones who inject the energy into language that keeps it alive. Children and adolescents, for instance, are more eager to play with language than adults, because their language patterns are not fixed yet. That’s also why we can gain a fairly native accent in another language as children and even teenagers (I had a student from India who came to Switzerland at the oldish age of 15, and was speaking Swiss German like no tomorrow).

Women have a greater sensitivity for language than men – perhaps because the word was the protection and persuasive power we always had, whereas money, status, physical strength, or tools of aggression were lacking for most women for most of recorded history. Be that as it may, it remains that women, particularly young women, are at the forefront of language change, and have been for a long time, not only jumping on trendy slang bandwaggons, but actually making those trends which, once picked up by the critical mass, become standard a generation or two later. Fridland amply shows how change is built in the language system itself, such as the vanishing of unstressed syllables across centuries. Ye olde sweete shoppe? You’d pronounce that ‘e’ if you were a contemporary of the great poet Geoffrey Chaucer in late fourteenth-century London. But not if you’re hanging out with Shakespeare at the Mermaid tavern 200 years later.

There’s nothing in the language itself that encourages (moral) judgment of any of its parts. It’s us – we, the people – who like to include and exclude, look up to and look down on others based on how they talk talk talk. And what does this have to do with the dots and dashes of punctuation?

Just as there is “proper language” there is “proper punctuation” according to some (read many, read most) people. Nothing gets people worked up faster than a misplaced mark which they can use to feel better about themselves. The Fowler brothers who wrote the best-selling grammar book The King’s English (1906) warn that ‘a certain gathering of commas’ is ‘a suspicious circumstance’, and that ‘anyone who finds himself putting down several commas close to one another should reflect that he is making himself disagreeable.’ They forget that punctuation rules are conventions that keeps changing across time and technologies with which we write. They are *not* inherent, particularly not in a language like English whose punctuation is mostly not grammatical but signals breath and rhetorical emphasis.

Just a tiny swirl of a mark, and look how it ruffles our feathers. Imagine now a mark that takes a stand, declaring “I’m here!”, and unapologetically so. The exclamation mark is probably the greatest magnet of anger, disdain, and outright hatred. It’s supposedly screechy, shrill, hysterical, loud, annoying, bullish, over-emotional, and just altogether too much. Too of everything, no thanks! Ah, did I forget? Too female.

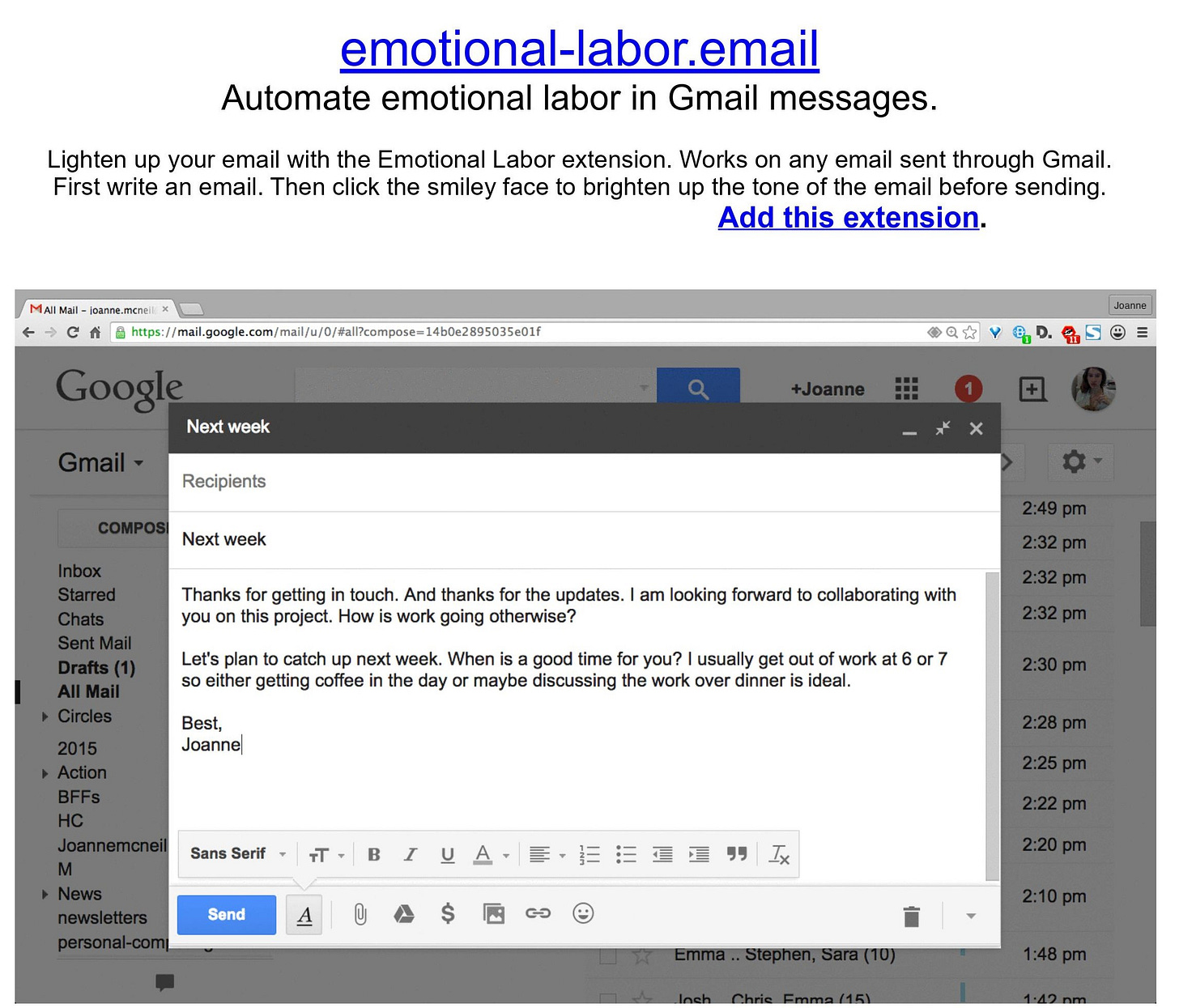

In 2015, tech writer Joanne McNeil developed an “Emotional Labour” Gmail extension, liberally sprinkling your sober messages with up to 5 !!!!!. This was a spoof as a reaction to news pieces on how difficult it is to communicate feeling and liveliness through computer-mediated messages.

On the other hand, the real extension (wait for it) Just Not Sorry helps you avoid ! and its nefarious villain-buddies like “I’m sorry” which, according to the developers, ‘undermines your gravitas’ and hence ‘makes you unfit for leadership’. Sue me, but I thought apologising was the mark of a grounded person I’d like to be around. Other so-called “warning phrases” the extension flags up for you to change are literally (well, see above!), just as in I just wanted to let you know, kind of, maybe, exclamation marks, and (mystifyingly) think. I used to think thinking was pretty essential, but there you go. Apparently, the add-on was downloaded more than 20.000 times. That’s worrisome.

The same story of judgment founded not on linguistic principles but social prejudice that applies to Fridland’s “bad” words concerns the exclamation mark: because women tend to use more !!!, they must be bad. Because ! bridges the gap between you and me across the blank digital ether, it must be untrustworthy.

(A little aside: there has only ever been a single study of gendered uses of !, it’s 17 years old, and emerges from the highly specific context of library studies. Linguist Carol Waseleski found that women did, in fact, exclaim more often than men, but those ! signalled friendliness and inclusion. Doubtlessly, “welcome!” sounds warmer than “welcome.” – I don’t know what’s wrong with that. Incidentally, male librarians used more !!! when they were angry and insulting. What we think is going on is actually not going on. The exclamation mark and women are getting short shrift, yet again.)

Researcher on internet language Gretchen McCulloch finds that a ! online expresses spontaneity and warmth. We use it in order to inject some life, presence, and personality into this cold and faceless flat-screen world. Exclamation marks are not a nuisance. They’re heavy-lifters of the punctuation-world. They’re the social glue between us.

¶

Our dislike and mistrust of any little rhetorical flourish is recent. As with so many things, it’s the fault of the eighteenth century (in the nineteenth century, things really came home to roost, and we’re the heirs today). In the Renaissance (my favourite period), rhetoric was king, because persuasion was. Anything helping you convince the reader or listener was fair game. Perhaps that’s also why the ! and half of its sibling still in use today originate from an inspired 200ish years (between 1350/1400 to 1600).

We shouldn’t use fewer exclamation marks. We should use more! We shouldn’t use fewer likes and totallies and umms. We should uhh away to our heart’s content.

Well that was much more interesting, enjoyable and thought-provoking than I expected!!!

I receved an email saying you replied to my comment but the reply doesn't appear here. According to the email you said, "Glad to know! What did you find most surprising or curious? 🧠👓📖" Well, I had never really considered punctuation at all, let alone how it relates to "verbal tics." But now it seems quite obvious that there is a connection. As an older person, I was taught with many of the attitudes that you mention. I was told there were hard and fast rules regarding punctuation and speech that ought not be violated. You seem to have a much more devil-may-care attitude on the subject. But I suppose the most surprising thing was that someone could be so enamored with punctuation!