Last week, I’ve been on a much-needed and utterly glorious holiday in the UK (hence the slight silence here!), soaking in all the culture the island has to offer – including Shakespeare’s Globe, of course. I’m usually one of the groundlings who hang around the stage, leaning on the planks, and getting up close and personal with the actors. That day, however, it was cold with drizzling rain, and I was tired out from walking, so I upgraded my ticket to a seat. Which was maybe not a good idea, because, it might have been helpful to remain close to the players for this production. It was in sign language. Partly, anyway.

The first time I heard about this circumstance was there and then in the playhouse. I can’t have been the only person clearly not realising this when buying the ticket, because people dropped off more and more as time wore on. And I get why. The production was bilingual, that means some actors speak, some sign.

Three big screens provided captions for the entire play (Anthony and Cleopatra). The Egyptian actors were deaf, the Romans hearing. Check it out here. In and of itself, I understand the underlying assumptions of this experiment: the play is, amongst others, about the clash of two great civilisations, about the military versus pleasure, the male and the female principle, and about love (and lust!), trying and failing to carve out a private space in a public arena. Lots of opposites rubbing against each other with their legitimate but mutually exclusive claims, so this bilingual staging does make for intriguing interpretations of the play itself: sign language means using all of one’s body for communication, as well as space around you. The Egyptians, already over-expressive as per Shakespeare, receive an extra layer of verve; the Romans, suited up literally and metaphorically, seem stiff, cold, and unpoetical. All voice, no body.

¶

The play’s director Blanche McIntyre believes this bilingual production somehow embodies the failure of understanding between the two cultures with Egypt clearly coming out on top, sympathy-wise. The Globe’s associate director Charlotte Arrowsmith explains the choice portrays the stark imbalance between a hearing world and a deaf subculture as it were, adding the pious wish for a world in which ‘everyone adapts equally and communicates freely’ (as per Globe blog).

I don’t see any of this working in this production, or even in the theoretical baseline.

All the characters – and definitely Cleopatra and Anthony – seemed to communicate rather well, and understand each other miraculously. If they had stumbled and hesitated and actually had conflict owing to miscommunication as part of the plot, Arrowsmith’s thoughts would make sense. As it were, the fact that there were signing actors didn’t seem to make any difference to the play at all, although it certainly did to the viewers. The crumbling of Egypt and the tragic end of the lovers didn’t originate in a conflict between deaf and hearing world, or in miscommunication of whatever kind per se, but rather between reality and dream, work and life, the inside and the outside. Production choices just didn’t hold up to scrutiny, and seemed more precious than authentic, more interested in virtue signalling than in thought-through theory. And this is all apart from the frankly un-enjoyable experience as theatre-goer.

As a hearing person, I would have liked to see the deaf actors signing their lines, but I was reading the screen with the Shakespeare text affixed to the upper galleries rather than attending to the stage. When the scene asked for a mixture of signed and spoken exchanges, I noticed my eyes flitting back and forth between the stage and the screen, not knowing when to look where (because I don’t know the play by heart). I found the experience draining and dreary, a failed experiment. I don’t like to admit it, but I fell asleep out of exhaustion…

But this event did have me wondering about punctuation in sign language. And Braille (reading and writing for the blind). Here’s your primer on feeling punctuation with all your senses!

¶

Sign language makes you animated. I can’t imagine how an introvert would feel signing, because you really need to express yourself with everything you’ve got: eyes, face, posture, hands (obviously). Just like spoken language, sign language has tone and pacing and something like punctuation (questions, shouting) through exaggerated movement or a pre-determined set of rules: in American Sign Language, for example, a yes/no question must include lifted eye-brows and a forward-leaning upper body. A “wh” question like “where” and “who” contains knitted brows and leaning forward. Have a look at this great video. Sign language is not just another manifestation of its spoken sibling, but a language in its own right with its own grammar; there is no such thing as a universal sign language; spoken and signed versions of a language may not be anything like each other.

So, tone and emphasis don’t need signed punctuation, but (just as in spoken language) an expression by non-verbal means like gaze or posture. There are, however, signs for punctuation marks as when someone reads out a text for dictation. And it’s imitating the shape of those marks with the hands. Perfectly sensible!

Danish comedian Victor Borge has created his own signed punctuation marks plus sound-effects in this sketch that I encourage you to watch, it’s beautifully old-school.

¶

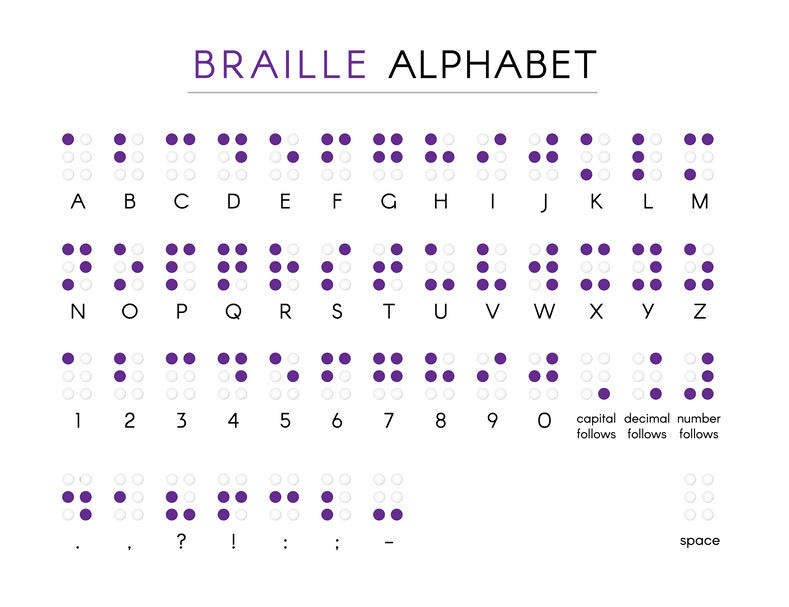

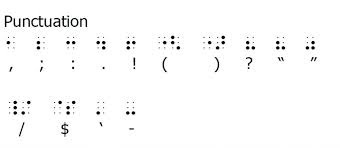

There’s another script based on expertise in reading with our hands, or rather fingertips: Braille. Tactile text for the visually impaired. It’s a system of touch relating to patterns of raised dots embossed onto a page. The dots are arranged in cells of 6, two columns of three dots vertically aligned.

Numbers and capital letters place a dot at a certain level before the letter, turning it upper case or signalling a number. Braille also has punctuation: it’s the letters a to j, but lowered by a dot.

The name Braille comes from its genius French inventor, Louis Braille. When he was three years old, little Louis played around his dad’s workshop and hurt himself in one of his eyes with an awl, a pointed woodworking tool used for making small holes. The infection spread, and two years later, Louis was blind on both eyes. Yet, both he and his parents were determined to create a future for him in a France of the early nineteenth-century that did not exactly offer many opportunities for people with disabilities. Doing very well at school purely through hearing, Louis won a scholarship to the prestigious Royal Institute for Blind Youth, where he excelled as well. At the institute, the children learnt to read through raised letters on thick paper, but this was a slow and laborious process. Surely there must be another way! And that way revealed itself during a lecture by Captain Barbier who explained to the children how he developed écriture nocturne, or ‘night writing’, as a way of helping soldiers in the field read messages without light which might give them away, or which they might simply not have. It was a system of 12 dots embossed onto paper which can be felt through the skin of the two first joints of the index.

What Louis did was to improve on the method by reducing the number to six dots in a rectangular cell, inventing combinations of dots for the alphabet, common words, numbers, musical notation, and indeed punctuation, including italics, and capitalization. When Louis completed his system, he was 15 years old. At first, he had trouble finding funding for his start-up in spite of pitches to the king and all sorts of institutions (including his own), but the medical establishment is slow when challenged. Braille writing really only took off after its inventor’s early death from tuberculosis at the shockingly young age of 43 years. Its main method never changed up until this day. And before there were voice recording computers, or Braille typewriters helping the visually impaired to write, people would put a grill onto the blank paper to keep the embossing straight, and punch dots into the surface. With an awl.

¶

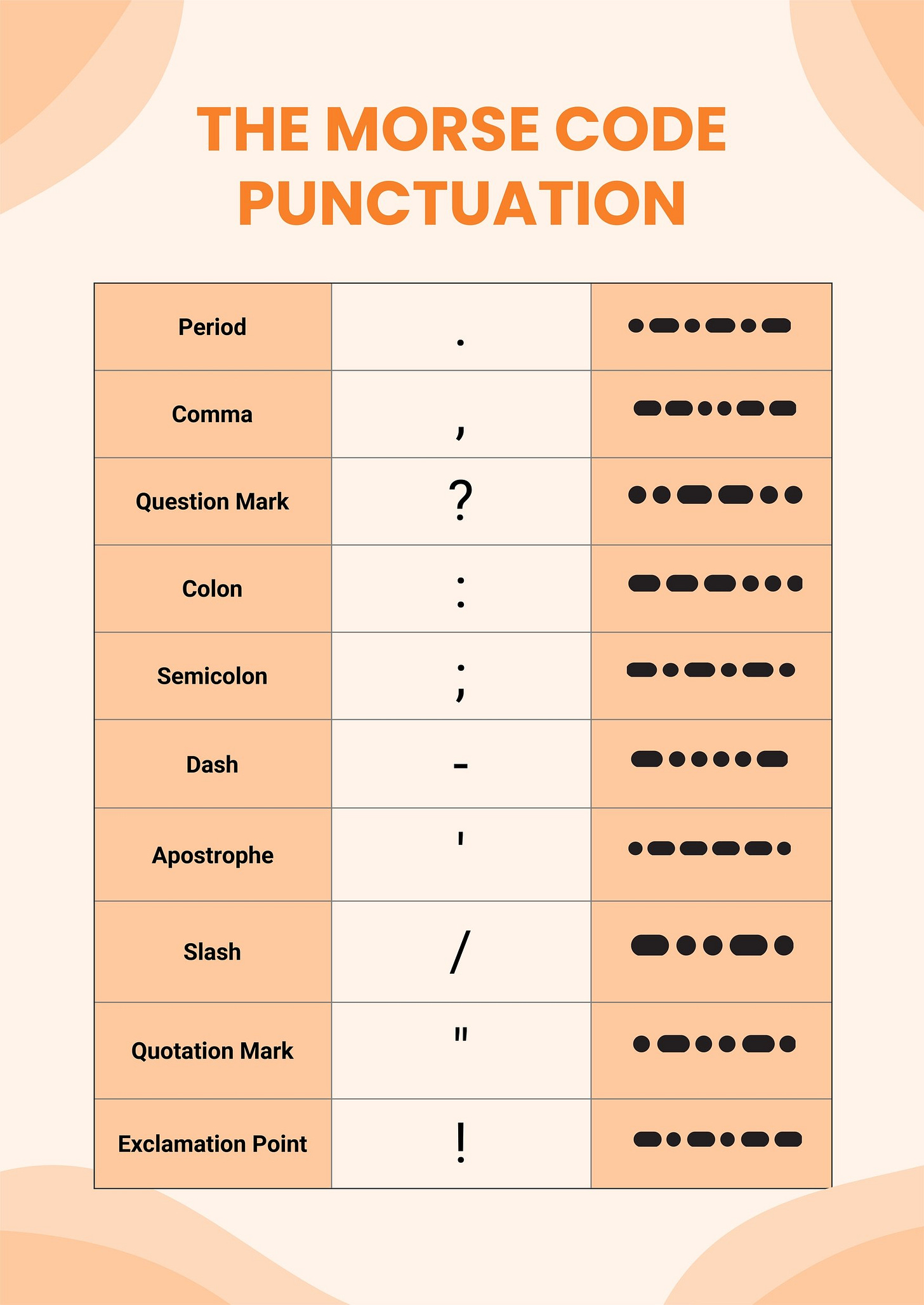

Deaf people see punctuation. Braille-readers feel it. And telegraphists hear it. There is a Morse combination for all common punctuation marks, although it wasn’t around from the start, since Morse code was developed for the most urgent messages only that needed to travel across vast distances, and those are generally understandable without the nuances of punctuation!

What I love about all of this is that punctuation really is universal. And that it packs a punch! Fingers slice the air, poke a hole into the invisible space between us, suddenly turning it tangible, experience-able. Punctuation makes space there.

Embossed dots on the page turn the etymology of punctuation into something felt: points (punctus in Latin) press themselves onto the soft fibre of the page, nearly piercing it. In Greek, a punctuation mark is called stigme, a mark or brand in the sense of a shape pushed into soft skin, perhaps by a hot iron poker…a tattoo. Remember that medieval manuscripts were made from parchment — animal skin. And, just like a tattoo, a punctuation mark leaves that. A mark, a memory, a meaning. And we apprehend it all with all our senses.