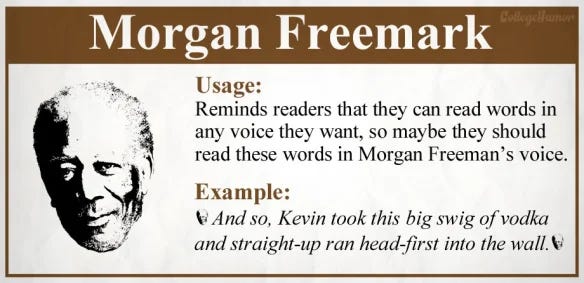

A Facebook group for language-lovers recently offered this gem.

This is a spoof from the website collegehumor.com, and probably relates to stuff I can’t even guess at (I’m getting incel gamer vibes). But the set-up’s believable: the fifteenth century was certainly a fruitful time for inventing punctuation marks with the printing-press producing more text and hence a greater need for traffic signs of text, printers focussing on readability, more schools teaching more people to read, and of course the semi-colon itself stepping into life in the 1490s. If anyone would have introduced another mark, it’d surely have been a mad monk in the mountains of the Kingdom of Navarre.

¶

At first glance, I thought this was a legitimate story - I was impressed by the pretty accurate definition of a semi-colon (somehow connecting sentences that are somehow related; but somehow they can also stand on their own; and this creates a breathless, floaty, dreamy kind of style) - but sadly it’s all made up. There’s no demi-colon (or hemi-colon, unless one refers to anatomical features of the digestive system). Yet, it’s perfectly possible we might want to invent a new mark or two in order to help us cope with the heavy responsibility of communicating through today’s technological devices.

Unless one counts emojis as punctuation, our repertoire of dots and dashes has remained relatively stable for a considerable amount of time. Our daily bread of full stop, comma, question mark, exclamation mark, and bracket was pretty much settled by 1600. The quotation mark took a little longer to refer to direct speech, and the semicolon and colon were sometimes used interchangeably. It seems we’ve been pretty content with what we’ve got (it took long enough to establish anyway!), but that doesn’t prevent us from experimenting and exploring. Writers, designers, and philosophers have proposed new punctuation marks ever since, and continue to do so today, sometimes as serious bids for improving reading and writing, sometimes (as in the case of the demi-colon) as fun thought-games. And sometimes both. Here are some of my favourites.

¶

Punctuation orchestrates three things: grammar, breath, and tone. New signs primarily intervene in tone, first and foremost that elusive beast called irony.

Put much too simply, irony is saying one thing and meaning another. Notably without pointing it out, else it’d be a poor piece of irony! Like explaining a joke, and thereby killing it. Yet, that’s precisely what irony marks intend: they want to clarify the subtext, the implicit meaning, the interpretation. They want to help us do our work as readers, alerting us that we mustn’t read literally here.

In 1668, John Wilkins, researcher and co-founder of an early science institution, the British Royal Society, worried over the slippery nature of language, and proposed an irony mark (an inverted question mark) in order to alert the reader that something beside the superficial meaning is going on.

Wilkins was followed by a whole host of other punctuation inventors such as the impressively-named Jean-Léonor Le Gallois de Grimarest in 1708, the French philosopher Jean-Jaques Rousseau at the end of the eighteenth century, satirical journalist Marcelin Jobard in the 1830s, and comedic writer Alcanter de Brahm a generation later.

There’s something about irony that just infuriates us! That makes us so nervous that we want to catch it, hold it, and fix, and for the last time. And punctuation seems like a convenient and economical way of doing so. Only, of course, that it seems we don’t like anyone telling us how to read. None of these marks have made it beyond the special interest history book (or newsletter!), which makes me think that we actually prefer not exactly knowing what a sentence means…

¶

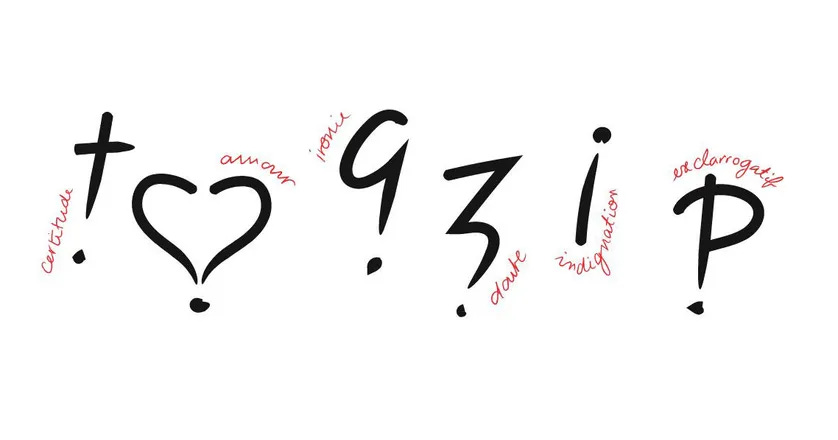

Well aware of the doomed project of punctuation renewal, French humorist Hervé Bazin gently mocks any such attempt by suggesting a handful of other “intonation points”, such as the love point (two leaning question marks forming a heart), the conviction point (a Christian cross), the authority point (‘like the sultan’s parasol’, Bazin clarifies), the acclamation point (arms stretched up in victory), or the doubt point (torn and unsure on which side to fall). Note, of course, the exclamation mark as versatile baseline form!

Recently, Austrian designer Walter Bohatsch revived Bazin’s brainy marks, proposing 30 abstract signs for abstract cognitive states (or feelings or actions), ranging from the palpable (contempt, outrage, or disappointment) to the less immediate (sagacity or seduction).

Bohatsch calls his signs typojis, perhaps because they function in a similar way like emojis: they comment on the text, rather than separate grammatical units or direct breath. He does use his marks in his private communication, and takes them as a serious proposal for ‘clarity and unambiguousness’. (You can listen to our conversation on typojis on my sporadically-updated podcast here.)

¶

Now, I love me some punctuation philosophising! I just think that the typojis are much too numerous in number, and much too abstract to be readily embraced by readers and writers at large. During the many years I’ve spent with punctuation, I’ve come to realise that it’s actually really really hard to change conventions. We humans are creatures of habit, and we’re lazy. We like things to be as easy as possible, while we also don’t like too much regulation. Declared projects to reconsider punctuation were and are always bound to fail. If change comes, it’s more likely to stem from technological revolutions.

Emojis are only still around, because we’re using texting technologies that make their typing easy and because their bright comic-y pictures are suitable to an informal chatty context. But would anybody writing a letter or note actually go to the length of drawing one of those elaborate detailed emojis like the gardener with a hat, dungarees, and a carrot? 👨🌾 Probably not. So, if new punctuation comes around, it’ll probably be connected to a change in devices.

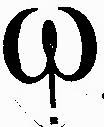

By the way, my personal favourite is the shit point or point de merde, dreamt up by French poet Michel Ohl (what is it with the French?! They’re clearly punctuation-adventurous!).

A “w”-bottom squeezing out an exclamatory dot. You can send this one to your local incapable politician.

And what do you think of the following marks we never knew we needed, but very much do?