When Romeo and Juliet see one another for the first time, they don’t yet know who they are, because Romeo and his buddies are crashing the Capulet party completely masqued-up. Juliet’s cousin Tybalt (the king of cats!) sees through their disguise, though, and feels offended, but Juliet’s father is in a mellow mood, and orders Tybalt to let the young ones be. Right after this exchange, Romeo and Juliet meet, speak, dance, and kiss, but Juliet’s nurse interrupts them. Both find each other’s names out through someone else, and are both shocked that they love the enemy.

Juliet tries to reason her way out of this dilemma, suggesting a name has nothing to do with the essence of the thing (she’s engaging in a centuries-old philosophical question we’re still asking!): ‘That which we call a rose/ By any other name would smell as sweet.’ The name obtains no inherent relationship to the object it refers to. It’s random, and so Romeo’s Montague last-name is just a co-incidence. No obstacle to love, then! 🌹💘🥀

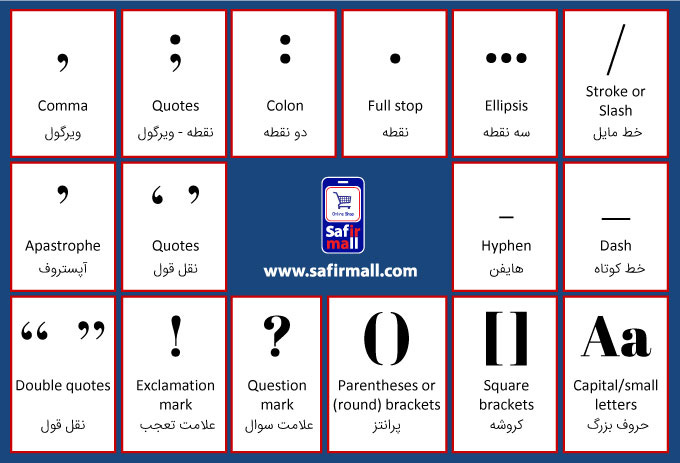

Sometimes there might be a relationship, though! In the case of punctuation, for instance. Punctuation terms in different languages can tell us curious things about our attitudes to what punctuation is and what it does. I’m proof-reading the German translation of my book on the exclamation mark this week (translated by a professional translator, not me, thankfully!). It appears with HarperCollins Germany on 21 January 2024 in case you need a gift for a German friend in a few months. 😅 So, this week I’m thinking about what is similar across the language board, and what’s not.

¶

Lots of languages of the world fall into two categories when it comes to naming those traffic signs of text: either a combination or other of the Latinate ‘punctuation’, or a combination or other of ‘setting signs’. There’s the French ponctuation, Italian punteggiatura, Portuguese pontuação, and Romanian punctuatie. Jane Austen and Lord Byron would have anglicised the Latin and called it “pointing”,

Those terms are witnesses to the origins of Western punctuation in the ancient Greek dot system, invented by Aristophanes of Byzantium, the head librarian of the fabled library of Alexandria 200 B.C.. For a longer explanation click here, the short version is Aristophanes introduced a system of dots to help inexperienced readers navigate text. And that dot, or punctus, or point stuck.

Punctuation is that which stings: in the Renaissance, the full stop was also called a ‘prick’, because the quill might punch the paper when finishing a paragraph. (Lots of things were called prick in early modern England… a pin, a bodkin to test if someone was a witch, the pointer of a clock, and also what you think it means.

Imagine now you’re a medieval monk, copying out the last book of the Bible in the flickering light of the candle; Revelations, the end of the world; the tip of your quill makes a little hole into the parchment, the hide of the animal, its skin your surface. A writer is also a tattooist. That’s why cultural philosopher Peter Szendi calls punctuation ‘stigmatology’ from the Greek stigma for (punctuation) mark. Punctuation marks leave marks, blue spots on pliable flesh.

¶

There’s punctuation and then there’s the Nordic group: German Zeichensetzung (‘sign setting’), Danish tegnsæting (‘sign sentence’), and Dutch lees teken (‘reading sign’). Similarly many miles away with Arabic’s alamat (‘sign’ or ‘indication’) or Persian’s neshan-e gozari (‘showing signs’, and alamat).

I love Urdu’s ramooz auqaaf, ‘sign of stopping’, because ramooz is the plural of ramz, meaning ‘mystery’ or ‘code’. Punctuation is the spell to unlock the secret of writing. Except for Urdu, all of those terms are distinctly mild in comparison to punctuation, speaking about what punctuation is (somewhat arbitrary ‘signs’) and the activity of the reader or writer (‘setting’ them up, ‘showing’ the grammar or breath). Rather than violating the page, we graciously navigate it through inky semaphore.

¶

Most world languages have punctuation marks. Those written from left to right, as well as those written from right to left. Japanese and Chinese ideograms, sign language, Braille (writing for the blind), even the world’s oldest writing systems, hieroglyphs and cuneiform, had rudimentary forms of punctuation. It’s a universal human impulse to shape words into some kind of order, grammatical or tonal. After spending many years with dots and dashes, I must say that they create as much confusion as they do away with, but any good human endeavour does that. What would life be without ambiguity anyway?!

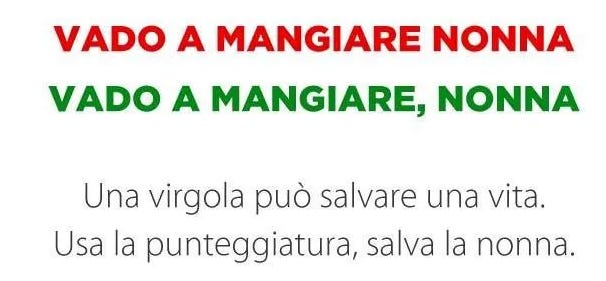

Sometimes, punctuation translates from language to language:

Sometimes, punctuation doesn’t translate. A language like German, for example, punctuates 100% grammatically, that means there’s little wriggle room for play with rhythm, breath, and tone. In German, you have to separate clauses from one another with a comma, else you make a mistake and teachers or the grammar police will pick you up on it!

“I think punctuation is fun!” for example would be separated by a comma (Ich denke, Zeichensetzung macht Spaß!). “I think” is one clause, and “punctuation is fun” is another. Technically this is helpful, because you see the joints and ligaments of the language’s skeleton as it were. And when I didn’t know English well yet, I certainly felt a kind of relief in letting my punctuation sink into the prescription of grammar. You don’t need to think beyond rules. Is that a bit German maybe?

Now that I’m older and wiser (well…), this is too reglemented for my taste. I like punctuation according to breath. And English allows that. It’s more capacious than German, because you can put a comma between “capacious” and “because”, but you don’t have to (no need for a pre-but comma either!). That means if I want a bit of a cleaner sober swifter look, I’ll go without comma. If I want to insert my voice a bit more, I’ll use commas as a guide to when I’d rest and breathe if I was talking to you face-to-face, hoping that you’ll imitate this rhythm with the voice in your head. There’s more presence in that. More personality, more intimacy.

These nuances sound overly nice and sophisticated maybe, but they’re real. We’re extraordinarily adapt at picking up those minute details, and at naturally using them to our advantage without even thinking about them. By attending to punctuation, we press the pause button for a short while, we’re curious about the nuts and bolts of language, we wonder and admire. And we put it all back together, and get on with our life, looking at it from a slightly different, slightly more aware angle. Juliet is right, perhaps. Punctuation by any other name would still be the code to unlock the miraculous mystery of text!