It’s October, that’s ADHD awareness month, y’all! And here a confession right from the start: yours truly is “one of those”. One of those creative but messy, blunt but adorable, unreliable but kind-hearted people with that so-called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. This description is not a self-assessment, it’s what I’ve heard over the years from others about me.

My ADHD is not so much physical but mental. For most of the day, my mind is running off into a thousand different directions, thoughts racing furiously on those famous German no-speed-limit-highways to…where? Never-finish-anything-land.

Don’t get me wrong: this is an amazing quality that I cherish in many ways, because it allows me to have sudden weird insights, connecting disconnected things in a manner nobody has thought of before (such as exploring the social history of punctuation!). People are always saying “we gotta think outside the box, outside the box”. But the thing is: there’s no box for me in the first place. That means I’m assailed by intriguing thoughts zooming by my consciousness all the time, and I’m like a Border Collie reacting to movement, I chase right after that juicy-looking idea zipping by. If your mind is constantly exploding into one firework after another – no matter how beautiful it is – you won’t get anything done.

¶

At the same time, precisely because my mind is an open field prairie, a kind of ocean of thought immersion, a strange multi-dimensional constantly morphing something-or-other, precisely because of that boundary-less-ness, nuclear fusions of ideas are possible. Thoughts flying around, colliding, melting, and emerging as a completely new creature.

That’s incredibly exciting to feel. And exhausting. And embarrassing. Whenever I go to a museum, my friends receive a barrage of messages starting with “remind me of this new idea for a book about…” a Swiss family of hangmen (the medieval sword section), a brief history of cups (dishes from ancient Persia), or the representation of dolphins across centuries (old maps).

Needless to say none of my museum-ideas ever manifest in tangible form. Needless to say deadlines become so flexible for me they might as well not exist, and the shame I feel makes being honest about another extension nearly impossible, worsening the situation all the more. I don’t have evenings, or week-ends, or holidays, because I’m constantly busy putting out fires. Not to speak of the acute feeling of pervasive under-achieving.

See what I did there? I distracted us from the main thrust of this newsletter: not the mixed ADHD experience, but punctuation marks, and which of them might be particularly helpful for us with different minds. Because, while it would be exciting, perhaps, to just be able to connect our brains and transmit thought from one mind to another, we don’t have that ability (yet? thankfully?), so words are an attempt at telepathy disposable to us. Written words, as we’re exploring in this newsletter, need assistance in organising themselves, and in communicating tone. That’s what punctuation is for.

Punctuation helps the thinker think and write, and the reader read and think.

Punctuation, I’d like to suggest, traces the movements of the mind on the page. It’s a kind of early cognitive science, a non-invasive analogue map of your mind as it is mind-ing. By paying attention to punctuation, we get a glimpse into another’s brain. And ours. And not only that, some punctuation marks offer more leeway to ADHDers like me: their operations are more conducive to neurodivergent thought than others. They offer sufficient structure for stability, and enough looseness for the ever-shape-shifting ADHD mind to feel comfortably wriggly.

Punctuation shows thought at work, and helps different kind of thought get to work. Here’s how.

A Movement of the Mind

Let’s think of some ADHD-related characteristics that we’ll thread into punctuation marks below: expression is big for people with ADHD, be that what we think or feel. Our emotional make-up is certainly more sensitive to upset, while it also means feeling and expressing joy, excitement, and enthusiasm more than so-called neuro-typical people. Distractability is a phantom of many names, including digressing, diverting, or day-dreaming. I like “mind wandering”, because that describes the activity without the judgment. ADHD minds love to roam. We can get lost in the meantime, and we can also find treasure along the way.

Mind-wandering is a huge field of research for all sorts of disciplines and questions such as the nature of creativity and intuition, meditation and mindfulness, managing mood disorders, memory studies – because why do we do that? Why do our minds wander? Where do they go? Why there and not there? How do we feel like before, during, and after? Which brain functions are working when our thoughts hike across Grey Matter Mountain? Does it have its place in our life, or is it utterly harmful? Do some people’s minds wander more than others? Can we control it?

¶

Overall, there’s constructive creative mind wandering that may unlock mental blockages, and there’s unwanted rumination, causing worry and regret. Both kinds occur when we’re not actively paying attention to what we’re doing right now, when we’re engaging in repetitive automatic tasks like washing the dishes, driving, or taking a shower. Our bodies are on auto-pilot. Then our minds fly!

The bad news is: mind wandering is largely out of our control. People with anxiety and depression report feeling worse after getting off-track, because their thoughts go to the past (“I should have”) and future (“I’m scared of”). Scientists recommend actually training our conscious minds to notice when our auto-pilots settle into the driver’s seat, and gently call our attention back to the present moment. Even if that’s standing in traffic. This is of course the essence of mindfulness.

The good news is: mind wandering makes your life better! Well, the right kind of it anyway…

Relaxing the mind means allowing it to do its thing without constraints. Free-wheeling like that is central to creative processes whereby numerous ideas ricochet around the endless space of our thought, generating and re-generating novelty again and again and again, and it’s our emotional system flickering on when an idea seems viable, hoisting the subconscious into the conscious. That’s intuition, a hunch, an educated guess: intuition is a magic formula of knowing your field, listening to your feelings, and giving yourself play time. This kind of mind wandering actually increases productivity (if we want to engage in such capitalistic terms in the first place).

Punctuation marks assisting such expansive thinking might just be good for all of us, not just for people with attention challenges!

¶

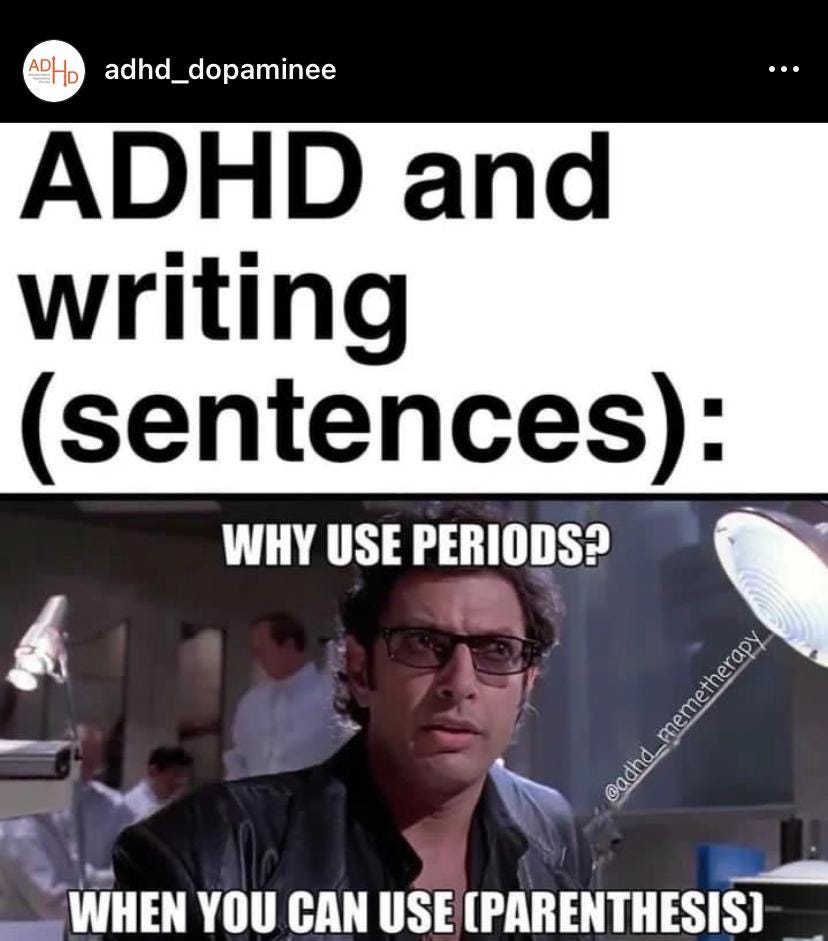

Wandering through Literature

It won’t come as a surprise that literature knows free time is good for us, and not only tolerates but actively enables and encourages mind wandering. One of my favourite professors at Cambridge, the incredibly erudite insightful and also kind and curious Raphael Lyne, has explored extensively what writing, and particularly Shakespeare, tells us about our minds. In his lecture “Shakespeare and the Wandering Mind” (2018, available online), Professor Lyne identifies pockets of opportunities for mind wandering in Shakespeare’s plays which, he suggests, are not coincidental, but purposeful: in the history plays about kings and queens and succession lines and challenged legal rights to the crown, characters tend to go into convoluted and confusing (bordering on the boring) chronicles of familial ties and legal nitty gritty.

Rather than paying close attention to content, we’re free to slacken our engagement here; zoom out, watch actors react; integrate, re-order, process, judge, remember. Shakespeare intuited that, and deliberately created such moments where our minds can do this important work. Excess and detail has a centrifugal drive outwards, so we get to observe from far away. Spinning into space is precisely how I feel like when I encounter old-school websites, or websites that just don’t care what your user experience is…

I really love how scholars like Lyne recuperate what today’s society considers useless and unworthy. Words. Too many words. Volubility. Prolixity. All those lovely terms for word-waves! Here’s a moderst proposal: let’s stop fetishizing the bare minimum for once; let’s not cut corners but provide even more padding around the edges; let’s not slice away in the name of “streamlining”, but entertain the notion that, perhaps, this is actually necessary even though we might not consciously know why.

It’s only been a century or so that we in the West have lost our fear of emptiness, horror vacui in art historical terms. Our not-so-long-ago ancestors as well as cultures around the globe both native and highly technologically advanced have always wanted to fill space with geometry, ornament, flowers, extra animals, soldiers, words. There’s no such thing as a vacuum in nature, why should there be in art?

A wide-spread belief of ornaments as talismans also conditions this fullness: busy patterns, many cultures believe, have apotropaic functions, that means, they ward off evil. Demonic spirits get distracted by sinuous lines hugging and knotting and whirling and swirling, so much so that they get trapped in the maze. I’ve written about the importance of additional non-sense syllables like umm and uh here, crucial to mental processing but demonised by self-styled speech coaches.

It’s really only four generations or so in the West that massive slabs of material without any decoration at all have become the staple food of art and architecture. I was once teaching French to the employees of a Swiss-German company producing glass fronts, glass walls, glass balconies, everything glass, and it was frankly an unpleasant experience to pass through their buildings to the office – everything was so…transparent. Nakedly exposed. So dead.

Today, our houses, our paintings, our texts, and our speech need to be sober, neat, concise, and robotic. And most of all minimal.

If you don’t remember anything from this post, remember this: a little bit of mindlessness here and there is A Good Thing.

¶

Punctuation for Expansive Thinking

How we write – and that includes punctuation as organisor – is an expression of the genesis of thought, of thought being born. One is not prior to the other, but conceived within and together with it. Looking at punctuation marks and metaphors and rhetorical tricks reveals the workings of the mind, and Renaissance people knew that when they composed manuals for good writing: in his Treatise of Schemes and Tropes of 1550, Richard Sherry claims the task of rhetoric is ‘to utter the mind aptly, distinctly, and ornately’. Language analysis is the neuroscience of the sixteenth century.

Feeding this into punctuation and ADHD, let’s examine some punctuation marks that both allow and foster expansive thinking.

First and foremost: the bracket! Also known as parenthesis. I have a particular relationship to parentheses because they were my first punctuation love. The basis of the mark (inserting additional matter into the main sentence) has been around for ever, but bracketed words had never been marked until the Renaissance. Roman rhetoricians already described brackets in their texts as matter that is “interposed” between other matter, but it took 1399 years and language-lover Coluccio Salutati to translate the phenomenon of temporary digression into typographical reality. The lawyer and writer added the first parentheses by hand into a text dictated to his secretary, that’s how important it was for him to include them.

¶

Brackets, whether (round), <pointy>, or [angular], instantly turn a flat 2D sentence into a spatial 3D syntactic body with volume and depth. Something else is going on at the same time, we’ve got two parallel-running lines of interest, kept apart through the visual walls of the bracket that helps us read considerably faster, but also connected by ways we’ve got to find out ourselves. Brackets contain clarifications of (or disagreements with) the main sentence, additional information, expressions of emotion, calls for attention, repetition of what’s important, examples, subversions. They instantly turn a somewhat simplistic, square, linear ducks-in-a-row sentence into an intricate controversial hot pulsing thought you need to actually engage in. You need to shuffle its parts around, see what fits where, like a magic rubix cube. Parentheses ask for incredible brain power from both reader and writer.

In his 1579 writing guide Garden of Eloquence, Henry Peacham describes the amblings of parentheses as ‘going out from order, but yet for profit’, and advises that ‘we must have a perfect way provided aforehand, and without long tarrying return in again cunningly’. So, rather than a symptom of a confused mind constantly remembering extra stuff and getting off track and cramming words into an already over-full suitcase of a sentence, parentheses actually show a master-architect of syntax at work, planning, projecting, pace-controlling.

It is certainly true that the parenthesis obtained a somewhat mixed reputation in the Renaissance (and maybe still today?), since its workings can be understood as both confused and complex: should the serial bracketter re-think their sentence and rephrase to avoid them, or does their scaffolded style enhance their purpose of persuasion? Anything was fair game for Shakespeare and contemporaries whose main aim of speech was influence, and so, rhetorician George Puttenham categorises the parenthesis among language tricks that create a ‘tolerable disorder’. It’s all a bit messy, but understandably enough to just about take it. And maybe for good reason! Or ‘beauty’ as Puttenham adds.

Parentheses, I’d like to propose, are amenable to ADHD brains, because our thoughts often run parallel; we think by association, so we like adding little extra details to the main matter, and the bracket helps accommodating for that while not completely succumbing to a new line of inquiry. And remember, of course, that a brief mental detour for mind wandering is natural and welcome.

The parenthesis is not the only punctuation mark dealing with additional information: dashes, semicolons, and points of suspense also engage well with butterfly minds, fluttering from one sweet-smelling flower to the next. Dashes and parentheses spill over into each other’s territory, and can be interchangeable if – like so – a dash couple embraces an insertion. Only that dashes strike the eye far more violently than gently elegant parentheses (it’s clear where I stand!).

One dash or several can signal a change of thought, or a sudden insight that needs to stand on its own, cut off from its preceding words both visually and syntactically. I know, I know – a flock of dashes feels choppy – use with caution – for example when you want to express emotional intensity – or mental restlessness, too fast to pour into conventional sentences – the hard thing is, how do we get out of such a dash-vaganza without tumbling over its horizontal obstacle course?

The dash is a helpful companion for ADHDers, when a new thought pops into our minds unbidden, and demands attention right here, right now. Can’t even wait for this laborious tracing out of parenthesis walls anymore – this! – now! Dashes offer a valve of instant relief to enthusiastic bubbly brains.

¶

Elements dashed off like that tend to be fragments rather than clauses or whole sentences. Lengthy bits that somehow connect, but somehow also not… those are a task for the semicolon. Ah, good old semicolon, so ambiguous, so beautifully unclear; how does it actually work; what is it actually good for; why should we give it the time of day at all…

Points of suspense (…) and semicolons combine well together, since they both trade in that most human quality: the reluctance to end. Today, we use semicolons between sentences that could be discrete, but somehow seem to have an umbilical cord of sense or feeling that we’re unwilling to clip, the keyword here being “somehow”: it’s more a question of style than a hard-and-fast rule, as is so often the case with punctuation. Usually, semicolon sentences are stand-alone, but they also contain clauses of similar structure, for example, it is true that the semicolon can be confusing; that it’s a little vague; that it encourages lack of rigour; that we can communicate without it; and yet, people tend to pick it as their favourite punctuation mark in surveys. Used in this way, the semicolon helps rhetoric emerge, both for the eye as well as the ear (we pause a little more on semicolons than on commas).

Semicolons are a mercy from the punctuation gods for people with ADHD, because they allow us to spin thought after thought after thought without having to clarify the relationship between them. This thought/sentence can be here, and then this, and then this. The twilight zone of whether or how they relate to each other feels safe, and takes the stress and pressure of my mind to have to marshal my expression into order. Whose order anyway? ; is a relief for my fried brain.

Humans don’t think in an orderly way, so the semicolon strikes me as the punctuation sign that’s most closely channelling the movement of thought itself.

¶

Hot on the heels of the potentially endless semicolon-sequence comes the dot dot dot (points of suspense or ellipsis). They communicate a pause, a gap, a breaking off, a trailing off, a loss for words, a threat, a suggestive wink wink, a soft bowing out of the conversation. Grammar is less at play here than tone and interpretation of the literal meaning. As for us attention-challenged peeps, those dot dot dots might just be the quintessential representation of what it feels lie to float off on a thought, daydreaming…

Some honourable mentions must include the emoji and exclamation mark (ADHDers have BIG FEELINGS that claim expression!!!! 😅), paragraphs, margins, spaces between lines, bold, italic, underline, ALL CAPS, and the gorgeous variety of typefaces. All the good stuff that’s not a mark itself but part of punctuation, organising text. Website creators out there, make it easy for our eyes and minds, please, and use the tools design and text offer to pre-structure the scary onslaught of wordswordswords on a screen (or page). Shout-out here to my fellow-language-lover and substack-writer Ettie Bailey-King who teaches using bold font for digital inclusivity.

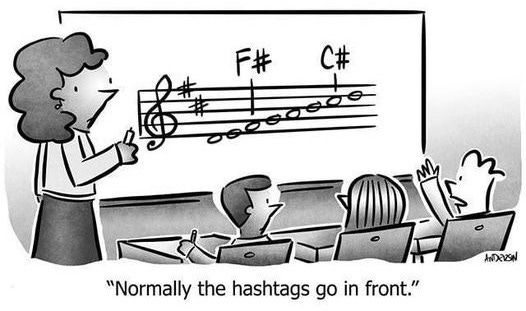

Among the less obvious punctuation marks we must not to forget the hashtag (as wider repertoire of non-alphabetical mark), offering a cheeky little pointer to something else. It’s like a mini-bracket but condensed to one word only, and it’s got to be a form of meta-comment. #irony

There’s more to the hashtag than meets the eye, working as it does by complex metaphorical association processes that require higher-level thinking. It’s like briefly opening the window to a hinterland of a new story – and then shutting it close again, because we’re not exploring that right now. A hashtag is a little teasing glimpse, a knowing nudge that, yes, there’s more for us out there, but for now it’s enough to just evoke that “more” to make a certain point. # helps me keep in line with what I want to say, while also satisfying my urge to rip open that window and plunge into the meadow of the adjacent story. It creates a little conspiratorial elbow shove shove between you and me, because I know that you know what I refer to, and you know that I know that you know, and the hashtag thus declares our in-group-ness. Think of #metoo.

That said, the hashtag comes with strings attached, particularly when we encounter it online. It’s a quick way to hyperlink, and hence an extremely slippery slope to tab-o-mania (I currently have 464 tabs on my phone, and 51 on my laptop). Like the asterisk *, or footnote [1], the # can send us on a wild goose-chase across the internet (or page, or book), requiring way too much precious mental energy to detach from, and return to the actual text.

We have reached the enemies of ADHD in the punctuation world: the period. The comma. The colon. That old and venerable trifecta of grammar is just too final and decisive for our darting mind. They’re too absolute. They’re bullets, killing creativity. Pins, fixing shape-shifting thought into one stiff frozen corpse. No movement, no life! What is there to say after a period? Nothing. Silence. We’re done. Emptiness. Vacuum. Remember, there’s no such thing as nothing in nature or in our minds.

¶

Of course, I love my dots and commas, and wouldn’t want to miss them. Likely, I would do well cherishing them a little more in the interest of finishing writing projects! The punctuation spectrum we possess today has not changed substantially in 400 years, which (considering the break-neck speed of communication developments) is a pretty long time. It seems we’re quite content with what we have, serving us well in occasions of finality, and occasions of expansiveness. We can harness the advantages of our diverse punctuation marks to individual situations in the same way as life asks for both narrow and loose states of mind, manners of expression. Punctuation allows us to shuttle between those, picking the right fit case by case. It’s a better force for diversity than any HR training!