I know, I know. We´ve just had two posts on asterisks and friends, beeping out naughty words. You probably have e-f***ing-nough of potty-mouthed punctuation, but hear me out: there´s more to an asshole – I mean asterisk – than meets the eye.

I´m deep into writing my second book, Points of Contention: The Social History of Punctuation – basically this newsletter but with more background and…more polite…due in a month (gulp!), and coming out early 2026 in the US, UK, and Germany. During the research, I came across some gems of punctuation play that I just can´t withhold from you for so long. This dot-and-dash-inspired creativity, it turns out, has secrets to whisper into our ears about language, thoughts, our imagination, and how we relate to one another when we´re not face-to-face. If we care to listen. Or see. Because the shape of punctuation is less random than one might expect from points and strokes that have neither sound nor sense on their own. So, here´s how an asterisk is like an a**hole, and why that´s a good thing.

¶

The World through Punctuation-Tinted Glasses

In her short story ´She Unnames them´, dizzingly packed with philosophical questions concerning language, ownership, nature, the human-animal relationship, gender, and the what-ness of things, eco-science-fiction-writer Ursula LeGuin has our mother Eve release all creatures (including herself) from the burden of names. Assigning a name to a living being, the story suggests, is doing it violence, is reducing its ever-changing fullness to one static snapshot, is putting up a barrier between the namer and the named, artificial and authoritarian and utterly bizarre. And yet, of course, we need to come up with linguistic referents for things out there for the sheer sake of survival. If survival is our goal (which the story neither confirms nor denies – read it, it´s just two pages!).

Some names and verbs have onomatopoetic roots, imitating the sound the animals are producing, such as insects buzzzzing, crows crawing, cockoos cuckooing, and cows lowing. Often, names attach to things because of their form: if we wanted to stay with punctuation, we could consider Apostrophe Island in Antarctica.

Here is Sican (mouse) and Ylan (snake) islands off South-Turkey, so called because the mouse rolls itself up into a ball, and the snake stretches itself out long – a game of all-too-serious hide-and-seek, perhaps? An exclamation mark, maybe? The earthly answer to a starry ? billions of light-years distant in far far (really far) away outer space?

The human impulse to give a name to what´s around us is natural and universal. We like to build a bridge between disparate things. It gives us safety. It soothes our nervous system. The brain is in love with making patterns emerge from the unpredictable, squeezing a drop of order out of the chaos of existence. Punctuation is no exception: a random blop of gaseous energy becomes a question mark, and a question mark turns into an astonished blinking eye. Where and how we recognise punctuation speaks volumes not so much about the world around us, but about our internal drive to connect and understand. It´s less a need to possess, I think; more a tendency to examine what we don´t know through what we know; comparing; inspecting the thing in all its aspects; by indirection find direction out as Shakespeare´s Polonius says in Hamlet. This is at the heart of metaphor-making: understanding one thing through another. Seeing an asshole in an asterisk, and a star in a sphincter.

For at least 400 years, there have been numerous plays, pamphlets, songs, books, and games on- and offline attempting to teach punctution through personnifications of different marks. My favourite one is Super Exclamation Point Saves the Day, and the acrobatic quotation mark quadruplets in the mid-Victorian Punctuation Personnified by a certain “Mr. Stops“ (picture below, quoting the ghost in Hamlet). Those pedagogical aids deserve their own newsletter, but are curious witnesses to the anthropomorphising tendency with which we treat punctuation, projecting human forms, behaviours, and qualities onto non-human beings or inanimate objects.

In a brief little poem on violence and tragedy in the Kingdom of Punctuation, German poet Christian Morgenstern describes a sudden riot against semicolons who are captured by (and in) brackets and killled in one fell swoop by the sharp minus-sign (or hyphen, I reckon). If this murder wasn´t enough, along comes impulsive dash, cutting off the comma´s head, effectively producing another semicolon, equally lifeless. The ! holds a hypocritically pathos-laden sermon before the thus-depleted remaining marks hop home on their one-footed dot.

Fifty history-heavy years after Morgenstern´s 1905 poem, another German, the philosopher Theodor Adorno, muses about the bodiliness of punctuation marks. In a 1956 essay, he compares the signs to traffic lights, musical instruments, and people, or rather body parts: the colon looks like a hungry ´mouth´ that authors need to feed with another clause, the semicolon´s curves resemble a ´drooping moustache´, quotation marks ´smack theit lips complacently, the ? seems like ´flashing lights´ on a car, and the ! is a ´menacingly lifted index finger´. Adorno who had Jewish roots and had to leave Germany intuitively disliked the exclamation mark, abused as it was by the Nazis not long ago (see my newsletter post here).

It´s interesting how Morgenstern saw actual bodies in the marks, moving and acting like people (soldiers or priests), while Adorno zoned in on body parts like eyes, lips, and fingers. This relationship between body and punctuation mark is not random, nor is the focus on the most expressive anatomy, including facial and gestural expressions. Punctuation is an ambassador for us when we´re not there; it´s our absent presence, infusing life into our otherwise impersonal writing. When punctuation isn´t only clarifying grammar (as it does in German, for example), but allows some leeway for creative self-expression, a comma, dash, and especially exclamation mark becomes our representative, our eyes and mouth and hands. Our gaze, smile, gesture.

Punctuation is our deputee, but it also orchestrates the body of the reader: it guides their breath, pauses, eyes, tone of voice, and emotion. As much as it regulates sentence structure, punctuation takes hold of our bodies, encoding them in text, and magically resuscitating them in every act of reading. And then there is, you know, the anus….

¶

´my sweet old etcetera´: Sexy Parts and Punctuation

It´s not a big step from eyes and hands to pussies and penises. Sorry, but you know that we´re not mincing our words here. Comedian Pierre Desproges (French, just sayin´) described the ! as “bital et mono-couille“, penal and one-testicled. During his first presidency, Trump liberally peppered his Tweets with !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!, causing journalist Julia Felsenthal to remark how she cannot unsee the exclamation mark´s pushy phallic thereness, much like the not-so-presidential presence of the businessman at the White House. The connection between punctuation and genitalia is older, though. Much older. And much more venerable.

Since the Middle Ages (at least for 700 years), “etcetera/etc./&c.“ means “that which is unspeakable“ for respect or prudishness. It could mean vagina, sometimes asshole, as in Romeo and Juliet, or the act of fucking itself, as in Chaucer´s Canterbury Tales. I´m not being rude on purpose, I wrote about it here. Etcetera continued to refer to the (female) hush-hushes well into the twentieth century attested in e.e.cumming´s poetry (‘my sweet old etcetera`).

Etcetera, as we´ve explored in a previous post, toys with the reader´s own primness. It says “come on, you know what we´re talking about, because you´re supplying in thought what the author is too reticent to offer up frankly“. Because it trails off, placing the naughtiness into the reader´s complicit head, etcetera is a great place-holder for textual genitalia. And perhaps it´s those two bulging curves of the ampersand & that inspire this innuendo of a certain kind.

¶

The parenthesis certainly offered cheeky writers of old plenty of frisky fun owing to its plump roundness. ( ) can stand as a visual representation of body parts, or what happens with certain body parts after different etceteras have been etcetera-ing together in unsafe ways. Playwright John Marston, for example, pressed both some harsh social criticism as well as reflections on Renaissance theatre and the print trade into one single parenthesis. In the 1590s, the London stage tended to offer history plays on royal bloodlines of the past and breezy romantic comedies. Certainly complex and nuanced, but also just a lot of fun.

Around 1600, however, something happened and things got darker: Shakespeare started composing his string of heavy tragedies around the turn of the century and during the first decade of the new, his friend Ben Jonson sharpened the tone of the Renaissance stage with his so-called city comedies (biting satirical commentaries on the follies and vices of urban dwellers), and John Marston upped the notch of bitterness considerably in his plays, ripping apart anybody in his way, from his neighbour to the king.

Some of the reasons for this turn may lie in personal history (Shakespeare´s son died in 1596, and he was probably reading philosophical treatises concerning scepticism, causing a deep questioning of everything). Some reasons were practical, since some of the playwrights started writing for a different kind of theatre than the open-plan ones with a mixture of patrons – smaller roofed performance spaces, lit by candles, and frequented by a better-situated kind of clientele who expected perhaps less warm laughter and more cynical smirking. Some reasons for the change in theatrical tone were political-historical: aging Queen Elizabeth, the virgin queen, was precisely that, a virgin who had no heir, and was notoriously reticent to appoint one, leaving the kingdom effectively suspended by her death in 1603. It all went well in the end (her cousin James came down from Scotland), but this uncertainty had been causing years of increasing dread and malaise.

Whatever it was, the early seventeenth century saw an unleashing of vitriol in drama, and Marston was at the forefront of it, having some of his work banned and burnt. The writer of an anonymous play described him as ´pissing against the world´, and he eventually got suspended from his own theatre company, because he had offended the king and the French ambassador. And not for the first time. Curiously, Marston joined the church after leaving the stage, and rose through its ranks until his death in 1634. One would imagine he´d have found his best material yet precisely there.

Marston´s parenthesis exists in his most famous and influential play, The Malcontent (printed in 1604). A stranger called Malevole (“of evil will“) arrives at the court of Genoa, stalking its rooms with sour face and harsh comments. He´s different because he doesn´t flatter or suck up to the duke, but tears everything down. It turns out that he´s the duke´s deposed brother on a revenge spree, eventually successful by evoking remorse in his formerly power-hungry brother. In the following scene, Malevole exchanges witty barbs with an aging lady-in-waiting whose name is Renaissance street-slang for female pimp.

Malevole and Maquerelle are sharing lines in the typical ballad rhythm (and they´re singing as the stage directions say). In that style, the second and fourth line usually rhyme. The ´golden locks´ of the Dane are supposed to rhyme with something connected to the Frenchman, only that Marston isn´t giving us the word. Our minds supply it, however, delivered as we are to the ineluctable magnitism of rhyme: the word is ´pox´, the Renaissance word for syphillis. The Dutchman is famous for being drunk, the Danish for his light hair, the Irishman for whiskey, and the Frenchman, well, for what people euphemistically called “the French disease“, because its first documented outbreak occurred a hundred years earlier in the 1490s during a French attack against Naples in Italy. Returning home, French soldiers spread the disease all over Europe, and while it´s not sure how and where precisely syphillis originated, the name stuck (similar to the Spanish flu misnomer).

But! Why the parenthesis? Marston (and the printer) could have left the space just blank, inviting the theatre-goers and play-readers to close the deliciously rude gap in mind. Was it a mistake as some editors and academics have suggested? Did the typesetter mean to add the word later and just had to include some type as a reminder to return to, which he promptly forgot? Did he not have enough blanks, and needed to make do with any type just to keep the line together? Nope.

The ( ) is neither an oversight not a forgotten typographic relic. It´s a smart visual joke, drawing on the developing conventions of play-printing, still in the making by playwrights like Marston and his contemporaries. The empty parenthesis invites readers to both think, hear, and see: their minds and aural imagination adds ´pox´, while their eyes can envisage an actor filling the empty space between the brackets and making a bawdy gesture on stage. They can also transform the punctuation mark into the actor himself, probably limping around the stage, since the two round signs bulging outward left and right are reminiscent of the bandy-leg symptom of syphillis. The parenthesis thus represents the body of the actor, the thing its holding place for (pox), the co-creation of meaning between author and readers, and an acknowledgement of the fact of reading a play (a contradiction in terms whose paradox dissolves once we consider the multiplied possibilities of meaning when performance meets print).

¶

In an earlier play, Marston similarly experiments with the parenthesis´s visual potential of a rounding body: the ridiculous Master Puffe courts Katherine while constantly interrupting himself to draw on his pipe. The printed text includes this stage business as numerous brackets, ´(puff)´, stalling his marriage proposal, but also setting the scene lively in front of the readers´ eyes. The dialogue itself draws attention to the smoking-induced delays, having Katherine counter that she ´cannot endure puffing´ -- smoking, but also her belly swelling during pregnancy. While this joke certainly comes across in a live performance where the actor can gesticulate with their hands and clothes, the parentheses on the page visually imitate the physical expansion of a pregnant woman´s body. The punctuation mark´s shape introduces physicality into the two-dimensional cognitive medium of the silent static page. And yet there´s more! Syphilis and pregnancy both witnessed the body out of order: pregnancy was certainly natural, yet Renaissance people believed the female body to struggle with imbalanced fluids at the best of times, let alone when with child; and syphilis wracked the body into distemper anyway with all its painful and repulsive symptoms of genital sores, ulcers all over, and deformation of one´s anatomy.

The parenthesis, curiously, signalled moderate disorder to Renaissance people. In his influential rhetorical manual The Art of English Poesie (printed in 1589), George Puttenham “Englishes“ classical rhetorical figures, calling the parenthesis the ´Insertour´. He groups it among the stylistic strategies working through interruption of the sequential flow of a sentence, thankfully categorising it as ´of tolerable disorder´, as opposed to others that are so ‘foul and intolerable’ that he ´will not seeme to place them among the figures, but do range them as they deserve among the vicious or faulty speeches.’ And then, as is often the case, Puttenham uses plenty of parentheses throughout his treatise himself, and never specifies which figures precisely are so awful and to be avoided.

It´s not that the parenthesis only accrued bad press – and anyway, liberal use by all writers in all genres belies the sound and fury against it – but authors and readers did find the two typographical curves germane to representing cultural attitudes towards a body in disorder.

¶

Bottoms Up! Brackets and Intrusive Reading

Bellies, legs…there are other body parts that are round and full…yes. Bottoms. Before parentheses conquered the printing of plays, they had taken over the pages of Renaissance writing a good generation earlier: from the 1570s onwards, texts both in print and manuscript explode into brackets, laying the groundwork for their adaptation into printed drama later on. Parentheses embraced authorial comments and addresses to the reader, seeking to break the distance between story-teller and listener. And they also toyed with the punctuation mark´s looks.

A particularly astonishing example of parenthesis-fun stems from John Harington´s long poem Orlando Furioso. Harington was a dashing, whip-smart, and utterly outrageous free spirit, shaking up the court of Elizabeth the first (and the literary scene) like few others back then. His poetry gained him attention at court (attention was one of the chief purposes of poetry for someone of his position), but also notoriety, and even a temporary ban from Elizabeth´s surroundings. In the 1580s, Harington tried his hand at translating excerpts of a famously naughty Italian poem. While probably entertained, the Queen was also strict, and punished her godson `that saucy poet` by sending him away from the court to his country house in Somerset. For ever! Or until he was done translating the entire work. Into verse. An unthinkable Herculean task!

Nobody expected him to follow through, but follow through he did. In 1591, Sir John Harington oversaw the printing and circulating of the first translation into English of the Italian Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto. But it wasn´t only that. Rather than make the racy Italian more palatable to a Protestant English mind, it made it racier. By far. Punctuation (and typography, that is, the design of the page) was one of the ways Harington went over-the-top in his fun and artistic work. (As an aside: he also invented the flush toilet, although the Muslim engineer al-Jazari developed a similar flush-device for hand-washing 350 years earlier.)

Ariosto himself flourished nearly 100 years before Harington (the Italian Renaissance occurred earlier than in England), a poet patronised by the brilliant Isabella d’Este of Mantua. Ariosto threaded together numerous story traditions the Renaissance inherited from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, imaginatively re-telling the story of a knight at the court of Charlemagne, fighting against a “Saracen“ (that is, broadly Muslim/Middle Eastern) invasion of Europe. There´s epic battles, romance, madness, death, sex, love, magic, tragedy, fantasy, globetrotting, space-travel – it´s hard to describe! And of course, plenty of subtle commentary on the social and political values of the day. The Italian poem, printed in its complete form in 1532, was enormously influential all over Europe, as was Harington´s translation for English literature.

Where Ariosto hints at nudity and sex, Harington goes right in, amplifying his description rather than coily withdrawing behind suggestions and allusions. An infamous instant of sodomy, for example, gains visual and interpretive significance in the English through punctuation: judge Anselmo travels across the world, looking for his adulterous truant wife. Stumbling into a forest, he comes across a gorgeous palace, guarded by an “Ethiopian“ (Renaissance short-hand for a black person) who claims it´s his. The Ethiopian shows Anselmo around the sumptuous bejwelled interior, offering it to the traveller, but not for any riches in the world. And yet, it would be his at no cost at all…just a little, you know… Anselmo rejects the man´s advances at first, but his avarice is getting the better of him, and he finally accepts being sodomised in exchange for the palace.

Ariosto soberly states: ´Sempre offerendo il merito il palagio,/ Che fe inchinarlo al suo voler malvagio´(´Constantly offering the deserving one the palace / Which made him stoop to his evil will´). Just as Anselmo agrees, his wife miraculously appears, and demands her husband´s forgiveness for her sins, balanced out by his.

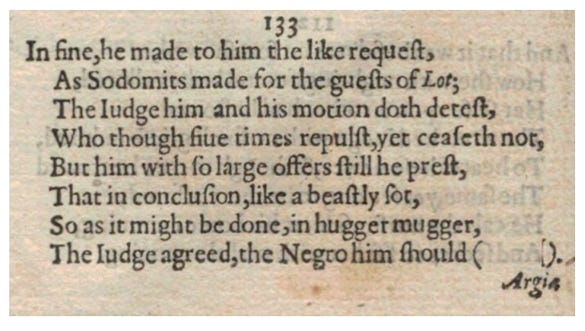

Here´s how Harington renders the passage thus:

´So as it might be done, in hugger mugger,/ The Judge agreed, the Negro him should ( ).´

Harington withholds the offending word – but, much as in Marston´s ´pox´ example, the rhyme scheme make it clear what we´re supposed to supply (´bugger´), and a coarse word at that. Harington also surrounds the vacuum of the blank page with a suspiciously butt-like parenthesis. As if we, the readers, not only thought sodomy, but also performed it ourselves with our eyes, penetrating the anus of the bracket through looking. Involuntary so, yes, but our choice to read in the first place means agreeing to such pitfalls and traps, set by the author through punctuation, pictures, and lay-out. Throughout his Orlando Furioso, Harington reflects on the nature of reading time and again, sometimes explicitly, for instance when he likens reading to ´chewing´, and telling prospective perusers to ´leave it alone´, and turn the page if they worry about the lascivious parts woven into the otherwise virtuous story. Sometimes, Harington gets us to reflect about what reading is through implicit means such as punctuation. Reading, for Harington, includes a voyeuristic element, as our eyes are captured by his design-choices, producing an illicit frisson that cheekily undermined the lofty humanist ideal of the edifying purpose of literature.

Harington was heavily involved in the printing process of his work, even correcting draft pages, and comissioning bespoke copies for circulation at court. The book as a whole, then, with its punctuation, marginal notes, image-text arrangement, title-page, and index are part of a greater whole, minutely curated to entice and tease us beyond words. Later translators of Ariosto, incidentally, felt so uncomfortable by the supposedly deviant sexuality of the scene that they changed the gender of the Ethiopian to female – Victorians, needless to say, standardising sexuality (and language) into right and wrong.

So, parentheses can refer to bandy-legged sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, and bottoms, to sex in all the various orifices, and to the holes themselves. In his novel about a science-fiction writer Breakfast of Champions (1973), American author Kurt Vonnegut has his recalcitrant protagonist sketch out an asshole as a kind of exorcism of the jumbled mind.

This sphincter looks like a star. An asshole-asterisk. Maybe Vonnegut is connecting the power of the anus and the asterisk to lead down a rabbit-hole of the unknown into the dark depths of… the inside of someone else´s colon, and the confusing centrifugal paths of footnotes. Maybe Vonnegut alludes to bleeping out something a**hole through asterisks, staunchly refusing to bow to censorship. Maybe he´s also just having a laugh. In all cases, * like ( ) lend themselves to visual meaning-making, infusing the body right back into the disembodied medium of the page. Or even more removed: the screen.

👓 Check in again here in two weeks for Part 2: from naughty to nocturnal punctuation. We´ll explore the same signs´ lofty aspirations!

¶

👉🏽 I take these examples from Anne Toner´s book on Ellipsis in English Literature. and Joshua Reid´s article ´Serious Play: Sir John Harington's Material-Textual Errancy´, both wonderful treasure-troves on punctuation and typography in literature between 1550 and 1800.

Always appreciate your valuable content.