When you walk into the huge and utterly breath-taking chapel of King´s College, Cambridge, you´ll be struck by the ceiling design, fanning out and down the body of the building in spiderweb-like cascades. At the centre of each node is a rose, set in a rose. The stone is sand-coloured, the typical Oxbridge ochre, so you can´t see the colours, but it´s the same rose, covering the dresses of Queen Elizabeth I on royal paintings where you will see a red rose, holding a white rose in its midst. This is the Tudor rose, symbolically making peace between the warring factions of the House of York (white) and the House of Lancaster (red) during the English civil war from 1455 to 1487. After the death of Henry V, that king of the Agincourt battle (´for England, Harry, and Saint George!´), two rival factions of English nobility vied for the throne, eventually pacified and reunited in the dynasty of the Tudors, starting with a Henry from the Lancasters and an Elizabeth from the Yorkists (Elizabeth I´s grandparents).

Shakespeare dramatises the recent-ish era of English history in his line of plays on monarchs and monarchy in the fifteenth century, just 150 years earlier than when Shakespeare was alive. In his plays on the Wars of the Roses, there´s a scene imagining the embryo of the conflict, the moment of split between York and Lancaster. The two dukes are quarrelling about succession in a garden, tempers flying high, threats are being made; then the Duke of York plucks a white rose from the bush around him, and encourages his followers to do the same; a supporter of the Lancastrians promptly plucks a red one. That´s Shakespeare thinking not so much about politics and history (though that, too) than about the sheer randomness of chance. The nobles picked roses, because they happened to fall out in a garden. If their fight had been in a stable, they might have chosen horses with a white or brown coat. If it had been in the armoury, they might have reached for a sword and bow. It´s random, that´s the point of it all. The choice is random and contextual, but through the act of choosing, the men imbue the objects they grab with meaning, retrospectively conjuring a story of necessity. It just had to be a rose. That´s not so. Meaning is what we make it.

¶

One might say punctuation is arbitrary, too, in name and shape. But that is not the case. As we have explored throughout this newsletter, punctuation is intimately welded to its context, material, historical, and human. People invented punctuation for a purpose, using certain kinds of surfaces and writing tools. WHENLETTERSWEREWRITTENLIKETHISWITHOUTSPACESBETWEENWORDS, the easiest sign to squeeze between kissing letters was a dot, and that´s what the father of punctuation, Aristophanes of Byzantium, the head librarian of Alexandria, suggested 200 B.C.. You want your punctuation mark to be easily distinguishable from surrounding letters to minimise mistaking a navigational sign for word. You also want it to be small and flexible enough to insert it post-facto, when the text you´re punctuating might be old, and governed by different rules and attitudes. But you also want your punctuation to be present enough for the eye to register, to linger on, to integrate into the reading process. It shouldn´t get lost or morph upon copying your text. Punctuation marks straddle competing tasks of transparency and conspicuousness, having to be there but not too much.

So, their shape is not altogether arbitrary, nor are their names, or how we call any literary and rhetorical figure. We live by metaphors, metaphors emerge from our lives and experiences in this human body.

In the last post, we explored punctuation marks, particularly the asterisk and parenthesis, and their relationship to the body, representing anatomical parts as well as sexual activity, and bridging the gap between attending a performance of a play live, and reading its printed text. The possibilities of * and ( ), Renaissance writers thought, were decidedly unruly. But the polar opposite was also possible: the very same marks reached for the stars. Punctuation can go from naughty to nocturnal, and here´s how.

¶

To the Stars and Beyond

The asterisk is among the very oldest signs invented for text navigation. After Alexander the Great died around 320 B.C., the Greek Empire disintegrated into independent kingdoms each ruled by his generals. While Greek continued to have an enormous amount of influence across Europe, Central Asia, and North Africa, its heyday of centralised power was over, and claimed by other budding forces like the Romans. Hellenic (Greek-influenced) Egypt, however, became a repository for Greek knowledge owing to the busy, diverse, and rich port-city of Alexandria where the monarchs built a massive library, gathering scholars and students, and half a million papyrus scrolls of all the best works of knowledge at the time. A kind of offline Wikipedia precursor.

The administrative effort to handle that many texts was huge, so the institution´s head librarians were researchers in their own right, constantly concerned with improving storage and retrieval, but also transmission of texts. Punctuation was one of the key players of augmentation, making writing more readable for non-native Greek researchers, and functioning as scholarly tools: different versions of the same story (such as the epic battle for Troy) circulated across the Mediterranean, so, for the sake of Greek pride, it was at the heart of the library´s endeavours to collect as many as manuscripts of the story as possible, compare them, and establish a chain of authority. Which text could be the most authentic? Aristarchos of Samothrace, the fourth head librarian of Alexandria, introduced the asterisk * in the margin to flag up duplicated lines, as well as omissions. The asterisk (“little star“) brings light into the darkness of textual confusion, so it´s no surprise the seventh-century bishop and etymology-collector Isidore of Seville offers a definition, suggesting that ´what seems to be omitted may shine forth. For in the greek language a star is called ἀστήϱ’ [aster]. There´s a lack in the text, creating ignorance – mental darkness – into which the typographical star leaps, brilliant and bright, stimulating our imagination to supply the gap, left by the metaphorical tear in the tale.

While transcribers would leave gaps in texts in the Middle Ages, inviting scholars of the future to fill up what´s missing if they stumble across a lost manuscript, Renaissance writers would insert stars. Because after the first rush of discovering old manuscripts between 1300 and 1500, the likelihood of hitting such a miraculous treasure shrank, and book-people preferred to establish visual representations of the situation rather than…nothing. Blanks. Paper gaps vulnerable to collapse, causing chaos in the text. So stars it was, then, to signal “ here be something missing“.

Compare these two editions of the Roman historian Livy, the first from the beginning of the sixteenth century, produced in the shop of the printing-superstar Aldo Manuzio in Venice; the second from the end of the century, printed in London when the scholarly apparatus of such a work was more established.

The first shows a chaste star-couple, alerting the reader to lost lines. The second confidently offers a potential completion that´s not officially accepted, surrounded by a burst of asterisks, hovering up and down the lines like space-dancers. Perhaps, Aristarchos´ choice of sign was random. Perhaps, * looked least like anything anybody would mistake for a Greek letter. And perhaps, he knew exactly what he was doing, bringing the night sky onto our pages here below.

¶

To the Moon and Back

When we look up at the night-sky (if light pollution allows us, and Musk´s SpaceX doesn´t clog up the big blue vault above us, we can see stars twinkling, and the moon reflecting sunlight – at least for two thirds of the month. The moon has ever exerted one of the most important influences over our human life: turning the tides, affecting our bodies (after all, we´re 60% water), symbolising the menstrual cycle that tends to take a month. The moon is a natural time-teller, waxing and waning reliably, growing from sickle to pregnant full-bellied milky-white, then thinning back to crescent that shrowds itself in the dark of the night – to do it all over again the next month. The moon means creation and destruction, re-birth, eternity, the feminine, time, marking time, mystery, the night, secrets. And so does the parenthesis.

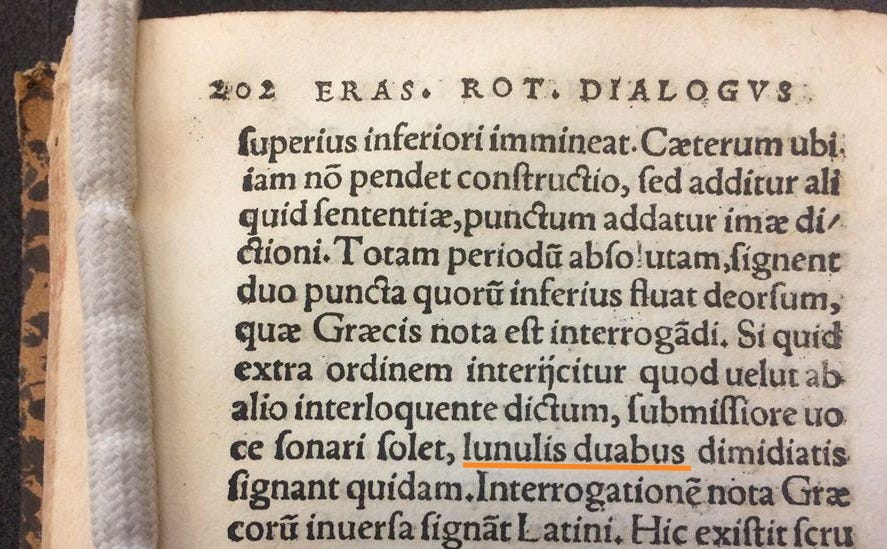

In the last post, bawdy brackets made use of their visual force as bandy-legs, bellies, and bottoms. But the parenthesis has a doppelgänger-identity as subtle and refined heavenly body. That´s why the great Renaissance scholar and educator Erasmus called them lunulae in his 1530 textbook on Greek and Latin, `little moons´.

As such, the convex-concave curves of the parenthesis cupped something said by the way, whisperings, secrets mouthed into the reader´s ear, mumbled under the author´s breath. For Renaissance writers, punctuation, in fact, belonged to the visual-grammatical, and the spoken-rhetorical. The school-teacher and writer of pedagogical treatises Richard Mulcaster called them necessary ´for the right and tunable uttering of our words´. Parentheses, Erasmus said, should be read our loud with a lower and faster voice, clearly communicating a difference in status and effect to the host sentence.

Both visually and aurally, then, what´s in brackets hides between the two signs. Something else is going on at the same time, running along-side the official story. That something is safe between the round walls of the parenthesis, protecting tender delicate qualifications and intimate expressions. Sir Philip Sidney, a contemporary of John Harington, was a master of such parentheses: in the 1580s, Sidney wrote a brilliantly stylish and dizzyingly chaotic story about two knights who fall in love with two princesses, and much mirth ensues, including transvestite faux-lesbian escapades. I mean really, what´s not to like?! The Arcadia was not printed in Sidney´s lifetime (he died much too soo from a war-wound, aged 31), originally circulating in manuscript. This is Sidney dedicating the work to his sister (a great translator and writer in her own right):

Here now have you (most deare, and most worthy to be most dear Lady) this idle work of mine: which I fear (like the spider´s web) will be thought fitter to be swept away, than worn to any other purpose. For my part, in very truth (as the cruel fathers among the Greeks, were wont to do to the babes they would not foster) I could well find in my heart, to cast out in some desert of forgetfulnes this child, which I am loath to father.

Sidney is hedging his words in ever more delaying parentheses. He adds simile descriptions (´like the spider´s web´ and ´as the cruel fathers´), classical allusions, and appeals to the reader (´most dear Lady´). He weaves a multi-dimensional carpet out of his words, encasing both intimate addresses and colourful comparisons in the parentheses which keep those vulnerable admissions safe and visually private. An open bracket is always twinned with a closed bracket; the words inside never left out in the cold; there is never just one side of the moon without trailing its mirrored obverse four weeks later; the parenthesis is a gentle kind of interruption, stable and predictable and balanced. Not so the …

¶

Darkness Visible…

The moon and the stars shine light into the dark affairs of humans. Yet sometimes, we want not less, but more darkness. If the parenthesis performs ´tolerable disorder´ with its interruption for a good purpose as Renaissance writer George Puttenham claimed, the Ancients (and thus also Renaissance people) had another set of ways on how to break speech off consciously. There was aposiopesis when you break off speech, and the reader or listener does not know what you mean. And ellipsis when you also interrupt yourself, but the interlocutor knows what you intend to say. As with the parenthesis and the exclamation mark, habits of speech and thought like emotional exclaiming, trailing off, or inserting extra words – those were stylistic devices writers deployed deliberately. Classical writing advice recommended their use; the Renaissance invented punctuation marks to make those devices visible.

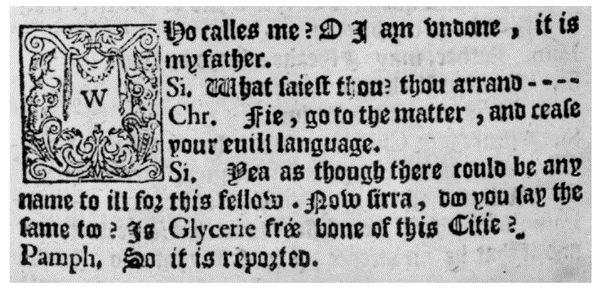

Dr Anne Toner has reconstructed the history of signalling purposeful interruption, tracing the earliest attempt back to Welsh dramatist Morris Kyffin who published a translation of a well-know Latin comedy in 1588 with a hyphen-series to capture breaking off.

Several times in the play, the typesetter uses three or four hyphens in a row to flag up the interruption which, in the past, would just fall flat in a non-grammatical full stop, or bleed into the white page without any punctuation at all. Quite disorientating for modern eyes! Kyffin´s invention spun off into the dash or several dashes for visually violent changes of thought or censorship, and into dot dot dots for trailing off, hesitating, alluding…you know what I mean… For an exhaustive exploration, see my post here.

Because dot dot dot and its various manifestations captured voice in motion, they became the favourite punctuation mark of playwrights and play-printers, because they capture voice in all its live inflections.

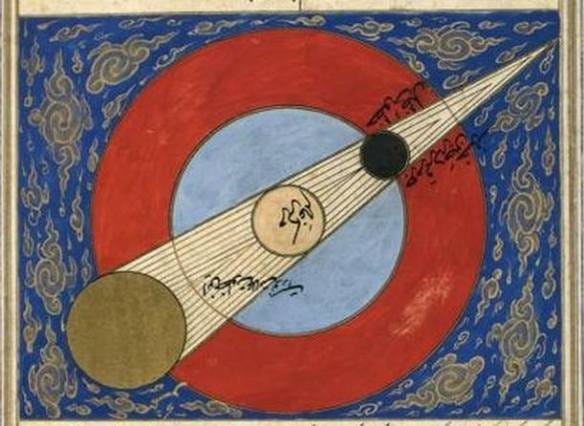

While aposiopesis means “being silent”, e(c)lipsis is “being absent”, to abandon, and to darken (ellipsis and eclipse have the same root, and were interchangeable back then). It´s not that what should have been there is no more – we´re supposed to be able to guess the conscious omission correctly – it´s rather that something covers something else, much as in the astrological event: the moon eclipses the sun, the sun darkens the moon. Two objects are temporarily congruent, the background shadowed by the foreground, the words by the dashes or dots. We don´t want illuminating stars or gentle little moons. We want the raw scary occultation of the three slashing strokes, three bullets. Dot. Dot. Dot.

King Lear, Shakespeare´s scariest tragedy (because least hopeful), moves in the shadow-realm of e(c)lipsis – in 1600 still a frightening confusing event. The playwright probably experienced one in his lifetime, or partial eclipse at least, such as in 1590 and in late 1605 around the time the piece was written. While the sixteenth-century (and particularly the early seventeenth) was a time of unimaginable revolutions in society, belief, knowledge about the world, geography, and technology (just think Galileo and friends), most people´s structures of thought and feeling still operated within received knowledge. And that meant that the sun´s sudden disappearance was a bad bad sign: it was a portentious omen, both causing and reflecting chaos in the world. The universe – and humans in it – were one delicately wrought clockwork, so if the heavens are in disarray, so will earth be.

King Lear dramatises such a disintegration of the social and political fabric, letting children turn on their parents, parents on children, and the kingdom splinter and sink into civil war, and in the midst of it all, an old man going mad. It´s a tough tough play, and while I love it, I know I can´t read or watch it when I´m in a raw place. Though perhaps I should lean towards it all the more precisely then. What else is tragedy for than to make the bad worse?!

Early on in the play, the Earl of Gloucester muses on the rumblings of the sky that have already caused rifts between King and Kent, a loyal courtier:

These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us. Though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds itself scourg'd by the sequent effects. Love cools, friendship falls off, brothers divide. In cities, mutinies; in countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond crack'd 'twixt son and father. […] Machinations, hollowness, treachery, and all ruinous disorders follow us disquietly to our graves.

The right and proper bonds of nature are disturbed, turned upside down, reacting to the imbalance in energy emanating from the eclipse. One of Gloucester´s sons, the illegitimate (hence) evil one, secretly scoffs at his father´s superstition:

This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are sick in fortune, often the surfeit of our own behaviour, we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars; as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical pre-dominance; drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforc'd obedience of planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whore-master man, to lay his goatish disposition to the charge of a star.

That sounds precisely like one of those men in their mid-30s I meet at friends´gatherings who mock me, when I very confidently say I am paying for weekly astrology readings (no kidding, I do). And whose face falls once I guess his star sign correctly. Touche!

When the illegitimate brother meets the legitimate one, he imitates their father in over-the-top complaints:

Behaving like a madmen (Tom o´Bedlam), the evil brother meets the good one, putting on an act within the time of the dash (an ellipsis cousin, as we saw, originating in the same family as dot dot dot). The dash/ellipsis really did ´portend divisions´, that is, after ----- the evil brother puts a mask over his divided self, pretending to be both gullible and solicitous towards his brother.

Dashes and dot dot dots really don´t forecast good turns of events.

Then there’s poor King Lear who, towards the middle of the play, is going mad with indignation at his disrespectul treatment by his daughters and court. He invokes the pagan gods of the play´s world, raging against the disloyalty of his own flesh and blood.

Lear breaks off on a long dash mid-threat. Overcome with outraged emotion, he interrupts himself, unable to continue, and perhaps unsure how. In the same way that the natural order of the universe is disrupted and de-ranged, so are relationships on earth and Lear´s own mind. So is language. The dash/ellipsis is both an agent of the literal and metaphorical darkness coming over the play´s world, and a relief: at least, we have ways of naming and representing the unnamable. The speechlessness of the blank can be scary. Punctuation is a mercy.

¶

Palaeontologist Genevieve von Petzinger has collected pre-historic symbols, preserved in European caves between 40.000 and 13.000 years ago. I can see a star. A dot. A line. And a half-circle. An asterisk, an ellipsis, a dash, and a parenthesis. Just sayin´.

So, is the shape of punctuation random or reasonable? Both, probably. A bracket can be boobs, bellies, bottoms – or the moon. You decide.