‘Only a Dot’: How Punctuation Circumvents Censorship

A little over a month ago, on 2 June this year, writer and translator Hosseyn ShanbehZaadeh was arrested for posting a dot under the Tweet of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The original Tweet, now taken down, shows the theologian and highest politician of the country together with a group of gold-medallist young sportsmen.

The Persian reads ‘This morning! A picture to remember the National School Volleyball team called “Martyr Sarda Zahedi” which recently became world champions in Serbia’ (my translation).

In a rare act of transparency, a regional prosecutor and a semi-official news agency have acknowledged the arrest three days after ShanbehZaadeh’s comment, stating accusations of espionage rather than punctuation provocation. Yet, it seems difficult to refute the coincidence of the social media post and arrest, particularly considering the sudden vanishing of ShanbehZaadeh’s profile on the platform.

ShanbehZaadeh had been a thorn in the side of the government before, spending several years in prison for his outspoken activism against the Islamic Republic’s system and politicians. Upon his release in April 2023, ShanbehZaadeh immediately continued his activity as critic of the government, detailing treatment in the feared Evin prison. As of now, 13 July 2024, his whereabouts are unknown.

So, why the dot? Why did he comment with a single full stop (or period if you’re from the US)? Why not words? And what’s the problem with a little . that it warrants imprisonment?

⚫

People on X/Twitter believed the Supreme Leader was furious because ShanbehZaadeh’s mere dot was ratio-ing his original Tweet, that is, outdoing it in engagement (before the whole convo was taken down, the dot had over a million views, 20.000 likes, and 1.500 reposts). So, perhaps Khamenei was envious that a Tweet containing nothing but the tiniest least in-you-face piece of punctuation was able to outperform his laudation of Iranian achievement. One Twitter user suggested everyone should ‘bombard’ Khamenei with full stops; another countered with a naughty punctuation-gesture (.!.), imitating both a provocative middle-finger (“fuck you!”), and a defiant erect penis (“suck my dick!”).

The full stop is not a known sign of protest either in Iran or elsewhere, although punctuation is a smart way to speak when you cannot speak (more below). It’s possible that ShanbehZaadeh intended to correct Khamenei who had left out the full stop at the end of the sentence. Remember that, technically, it’s not necessary to close a Tweet or any other message on social media with sentence-closing punctuation, because the discrete nature of each message makes it clear that the utterance is at an end: the givens of technology function like a blank paragraph line or like a full stop in and of themselves. There is something to be said, however, about a country’s official organs and high-level politicians hewing close to “proper” writing rules, so perhaps ShanbehZaadeh intended to call out the Supreme Leader, thus casting doubt over his intelligence (because incorrect punctuation and spelling is an easy way of shaming and ridiculing). By the way, and for the record: as Iranian who intends to visit the country again in the future, I hereby officially declare I do not have an opinion on any of this. I’m just describing…

⚫

Another reason for ShanbehZaadeh’s choice of comment may be that he calculated on the Islamic Republic’s well-known tetchiness: anything other than praise inevitably causes authorities to come knocking on your door, and the activist had changed his Twitter nickname to his real name shortly before this incident, so it’s possible this was a pre-meditated stunt, a trap and the government walked right into it. Appropriate headlines followed suit, drawing a connection between the minimalist nature of a mere dot and the outsized response of silencing, incarceration, and total disappearance. The Britain-based news channel Iran International reported the incident as ‘Iranian Security Detains Writer Blogger for a Dot’. American-funded Radio Free Europe titled its article ‘Iranian Blogger Detained After Posting Only a Period’. Najem Wali, Vice-president and delegate for the Writers-in-Prison scheme of the German branch of the international writers association PEN, similarly downplays the role of the dot in ShanbehZaadeh’s arrest (my translation):

‘The fact that the regime is afraid of even a simple full stop shows in what kind of panic it finds itself, and to what degree it represses people. It also shows how weak the mullah regime is and how its power is crumbling.’

This is a curious comment to me for two reasons: Iranians themselves would never allege the Islamic Republic is crumbling at all. Its power structures are in place as firmly as ever if not more, and it’s perhaps the West which likes to pretend otherwise to its own public for so many reasons (one of them being the convenience of exercising itself on an obvious enemy, while creating stories of impending political upheaval that, while having no basis in reality, feeds the self-identification of the oh-so-liberal Western system that Iranians supposedly prefer).

The PEN man’s assessment is also astonishing, because to call the full stop ‘simple’, hence unassuming, unthreatening, and not in the least scary or cause for respect runs counter what ShanbehZaadeh’s is trying to do in the first place: exemplifying the power of text, that is, all signs and symbols, characters, and glyphs belonging to that world of writing. Wielding them with precision and power. Exposing their weight in spite (or because?) of their relatively small size. Infusing them with meaning when they don’t have any of their own. Or so it seems. Here’s what I mean.

ShanbehZaadeh’s dot is obviously not “just” a dot. It’s a tool to circumvent censorship, to speak when you’re not allowed to speak, to speak even louder than if you were using words. Punctuation can do that, can be that, that amplifier, precisely when words lack. Simple? Anything but.

⚫

Words. Language. Sounds strung together to refer to things out there, or thoughts and feelings in here, is one of the behaviours unique to humans. What happens when words dissolve, either because someone drops them into the acid of repressive censorship, or because they fail to express our consciousness? When the beautiful structure of a text has disintegrated into the memory of the former building, into punctuation-ruins, and we become archeologists, brushing off stumps in the doomed attempt to imagine previous glory? What happens when we don’t have the body anymore, just some bones here and there, witnessing a once-intact skeleton, now no more?

When this is the case, punctuation marks become relics. Left-over fragments that we guard and cherish, even sanctify, looking to them for guidance like a lighthouse in the dark, announcing the safety of the shore.

These are metaphors, of course, because in the Iranian dot case, as well as the poem we’ll pick apart below, there have never been any words. Just punctuation. And yet, of course, we’re dealing with phantom words in now white, once black ink (or whatever digital substance letter-colour is made of in the world of screens). Free-standing punctuation, whether it emerged with or without attendant words, always calls up the ghosts of text past somehow or other. Or rather the potential of it. And the question. Why? Why no words? Who took them? When? So beware. There’s no such thing as “just” a dot.

Punctuation on its own can be a powerful sign of protest as in a European Parliament session in Strasbourg in 2013 when delegates held up exclamation marks in protest of Hungary’s constitutional change that conferred undue amounts of power to its central government.

I have written about the dot dot dot (…) points of suspense on posters of demonstrators, expressing their speechlessness about Germany’s complicity in the genocide in Gaza here. And then there’s a whole poem about missing words and protest punctuation.

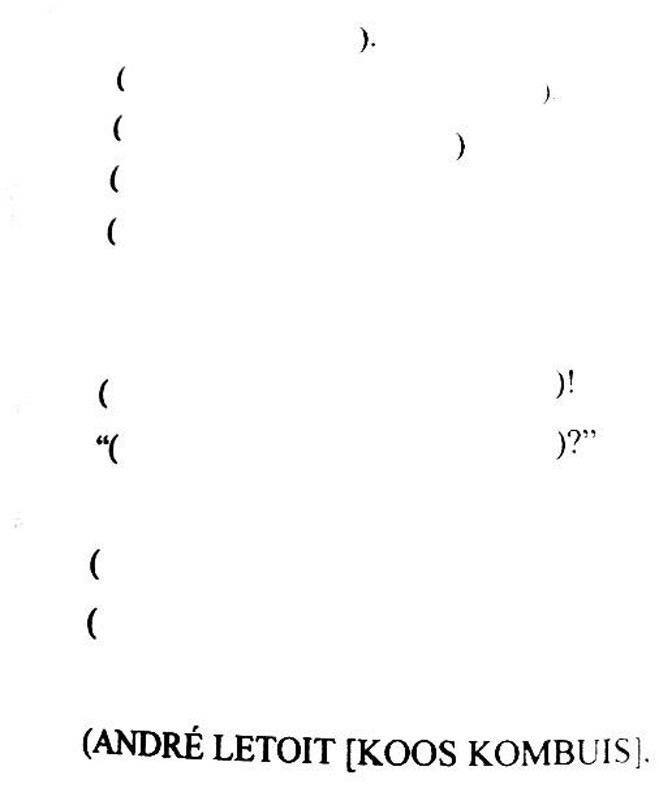

If you’re confused, so were Cambridge English students in their 2014 exams. They were set this poem (if it is one, as some news outlets have contested) with little other information. Some thought there had been a printing error, and the words had gone missing (not true, but pertinent). Some were outraged to be asked to interpret a poem without any words – how should one do that?! A student sneaked a photo out of the exam halls, leaking it to the student newspaper, and off it went to make the rounds among grown-up media.

The BBC reported of a ‘poem consisting only of punctuation’ (sober and proper); the Mirror was a little more, shall we say, expressive in their choice of headline: ‘Poem with NO WORDS leaves students baffled’. Nice eye-catching ALL CAPS, Mirror! Blogs picked up the story here and there with damning conclusions about the ‘non-existent poem’, or ‘the poem that meant nothing’. Is that really so? Is a piece without words really empty of substance? Or is it perhaps our own pre-conception of how a poem must look like that’s the problem here? Our inability to encounter something different, to tolerate discomfort when we come face to face with oddity, distress when meaning doesn’t offer itself immediately on a plate, but requires us to exercise patience, sit in ambiguity, and cajole the poem to release some of its secrets… nothing like a bit of punctuation to practise discernment and accept uncertainty. A brain-teaser if ever there was one!

Let’s replace judgment and dismissal with curiosity and openness. Firstly, I can attest that Cambridge students have around 15 to 20 poems to choose from (they need to write three essays on three questions in three hours). I know that because I sat those exams many moons ago. So, nobody forces them to pick this particular poem. The news reports online only show the poem and the name of the poet, not any other information students may have been given. I imagine the title of the poem was printed, too, but I want to keep it back a little and first look at the piece without any such clue. Ready for some close-reading?

So, I can see something that looks like a poem, because its outer edges (signified by parentheses milestones) are arranged in left-justified lines. If the parentheses hint at lines, then I can maybe identify ten. I’m somewhat confused about the upper part of the poem, because I’m not sure which parentheses correspond to which, and it seems the third one on the right does not belong to either the second or third one on the left, so is kind of hanging in the middle. I don’t think this needs to bother us unduly, and perhaps such sliding and undoing of the seams of the poem says something about what it tries to do or express.

Let’s say it’s a poem whose lines entirely consist of parentheses, some of them without pairing, notably the first and last ones (but also two in the middle). I’m puzzled by the other punctuation marks outside of the parentheses, but perhaps they are there to flag up the existence of an official narrative as opposed to what is being said in parentheses. There is an exclamation, followed by a quotation, and a question. I’m wondering whether this poem captures a conversation, or whether the quotation marks embrace a quotation from elsewhere.

The poet could just as well have chosen to signal the beginnings and endings of the lines with regular line-ending punctuation, as indeed he does (the comma, the full stop, question mark, exclamation mark, and quotation marks). So why parentheses? Parentheses hug sets of additional words which can escape from the sentence that carries them without causing it to collapse. Haters consider them extra stuff, and hence extravagant, unimportant and inessential, but that’s of course not true at all. The juicy bits are happening in parentheses more often than not: doubt, or criticism, or other kinds of qualifications of the “official” line the main sentence pushes. Some parentheses can get quite long, so long in fact that they challenge the main sentence’s claim to “main”. Such competition is right up the street of our poem’s interest in upending expected literary conventions: suddenly, what’s inside parentheses is at the heart of it all, what ever “it” means.

Parentheses also hold secrets. Their half-moon walls left and right visually protect the matter inside, opening up a space for subversive cognition, off-track ideas, deviance of all sorts… Poems don’t need to be coherent or understood; they just need to make us think. Maybe poems read us more than we read them.

So, without knowing any other context, what could this poem be thinking about? It could be thinking about what is a poem. What does a poem need in order to be one, be recognised as one. It could be about how we make meaning, about how absence creates meaning. It could be – and is – about how to mark something that’s missing. When something is gone, what is left behind? Nothing at all? Something unseen? Has it ever existed? Can and should we remember former presence? How?

I honestly don’t have answers to this, but I really love how this puzzling poem raises all sorts of philosophical issues concerning art and life. Also, of course, poetry doesn’t need answers, isn’t interested in them, only in questions. The piece is as open-ended to interpretation as its last open parentheses: feel free to insert your own thoughts and close it! Or not. Join the poetry!

⚫

Now. How would your interpretation change if you knew the poem’s name?

‘Tipp-Ex Sonate’.

Tipp-Ex, as us pre-1995 babies remember, is a brand of text correction when we were still writing by hand or typing on a mechanical typewriter, not a personal computer totally changing our relationship to error and its traces. As a child, I loved squeezing the sticky white Tipp-Ex fluid out of the pen, blowing on the line until it was dry, or what I thought must be dry, then tapping the tip of my index finger lightly on the spot, and realizing that, no, I had under-estimated the time it took to become over-writable. Looking back, it was nice to come home from school with inky fingers and Tipp-Ex dots. Actual writing had been going on. Our hands are much too clean today!

Before going onto the Tipp-Ex resonance, let’s consider connotations around ‘Sonate’ a little: a sonate is a piece of classical music with set parts. Andre Letoit going under the pseudonym of Koos Kombuis is also a musician, so perhaps this tells us that there have indeed been words inside those parentheses he used to sing. I’m a literary critic by trade, so I immediately think “sonnet” when I hear “sonate”, both pronounced in the same way. A sonnet is a specific form of lyric invented in the late Middle Ages, and perfected in the Renaissance, originally about love, originally 14 lines rhyming in pre-determined ways. The sonnet is an old and venerated structure that’s seen a lot of stretchings and experimentation across the centuries (by Master Will Shakespeare, for one), and while we have fewer lines in the ‘Tipp-Ex Sonate’, and no words to rhyme, and generally few reference points, I cannot but wonder whether we’re encouraged to remember the sonnet tradition. Are we re-writing (literary) history? Re-defining the ingredients of poetry? Alluding to old forms that have run their course today, now empty, because all words have already been said a long time ago? Perhaps.

And then, of course, there’s the Tipp-Ex. It suggests someone covered over words that they consider mistakes, or not relevant anymore. We can write over them. This reminds me of the medieval concept of “palimpsest”: parchment made from animal skin was incredibly valuable and expensive, and so rather than acquiring new writing material, scribes would scratch off previous text as best as possible, and write on top of the cleaned surface. Only that this sometimes didn’t work very well, and the old text would shine through, making for some interesting double reading, and raising questions concerning past and present words co-existing in one medium.

Perhaps the tipp-exed bracketed words are secrets…perhaps they’re dangerous. Forbidden. How does our interpretation change when we know that Koos Kombuis is a South African anti-apartheid activist? White Tipp-Ex silencing black words. Hosseyn ShanbehZaadeh would not be baffled by this poem.

‘Tipp-Ex Sonate’ is from the 1980s. After racial segregation came to an end in South Africa, Kombuis published a second version of the poem – with words. A hymn of unity in diversity for the rainbow nation.

When you encounter punctuation marks in the wild: don’t mock them. Don’t under-estimate them. They command respect. They may just point to a hinterland of power and politics we cannot possibly dream of. It is a privilege to speak and be safe. As Iranian, I have always known that. As German, I am witnessing rights of free speech being aggressively cut, and boldly so, as we speak. It is our duty to defend our words while we can. Let us not rely on dots and brackets to trick the censor when it’s too late.