Punctuation before Punctuation (Part II)

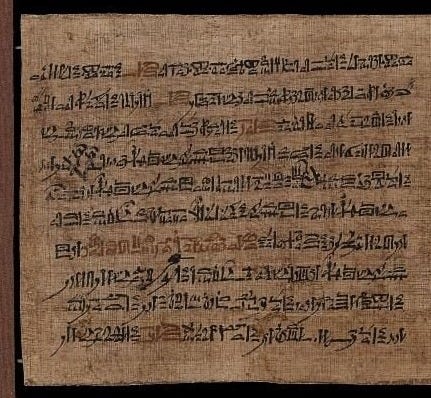

Punctuate like a Pharao

No! No, God, no! NOOOOOOOOOO!!!! [insert mental image of Michael Gary Scott’s reaction when Toby returned from Costa Rica to replace Holly as HR rep. A day without Office references is a day lost!].

Emojis are *not* like hieroglyphs as I have claimed here. Emojis are many things (mostly still a mystery to us), but they’re one thing definitely not: language. Script. Emojis partake of some functions of language and writing (and punctuation), but they are not any of those categories.

(1) They can be icons (simplified representations of things in the world).

(2) They can be symbols (representing an idea based on convention, e.g. 🩷= love).

(3) They can be metaphors, especially when they interact with words.

I love and adore emojis, but they are not a language and not writing. I’m willing to have a fist-fight over this!

Hieroglyphs, however, are a system of writing that draws on pictures, it is true. And it also has an early form of punctuation whose function is precisely the same as that of all of punctuation that’s ever been invented from comma to colon to quotation mark. Dividing text to make it more readable, and helping inexperienced readers. Plus ça change!

𓃠

What are Hieroglyphs?

Much like cuneiform, hieroglyphs are:

👉🏽 logographic (an image represents a word)

👉🏽 ideographic (an image suggests an abstract concept)

👉🏽 syllabic (images stand for the initial syllable of the words they represent)

☝🏽 unlike cuneiform: alphabetic (an image betokens a single consonant).

As in cuneiform, individual pictures can also act as modifiers of ajacent hieroglyphs. They were a mixture of all of the above, so had some functions of our alphabetic script today, but are still very very different.

When cuneiform pushed into its more complex phase of syllabic representation (rather than “just“ logographic script) around 5000 years ago, hieroglyphs emerged in Egypt. It’s unclear whether or in how far Mesopotamian writing systems have influenced Egyptian hieroglyphs, but it’s hard to think that there was no cultural exchange between highly advanced civilisations relatively close (sort of) to each other.

It took Mesopotamians 3000 years to develop a more flexible and sophisticated kind of writing from functional recording of goods, a long gestation history that hieroglyphs do not have, or that Egyptologists have not yet been able to discover and reconstruct. Perhaps, hieroglyphs are derivative of cuneiform regarding the notion of writing in the first place, yet its signs are original: rather than the abstract Mesopotamian wedges, hieroglyphs are pictures, drawn from Egyptian life such as the ibis, crocodile, and papyrus.

𓃠

Hieroglyphic Punctuation

Just like cuneiform, hieroglyphs don’t show the marks we´re used to today like dashes and question marks, giving us nuanced information on sentence structure and tone of voice, although they do have text-arranging devices such as straight lines surrounding the entire text-picture construct as a kind of visual formatting.

Apart from boxing a hieroglyph chunk, a well attested visual script-design was rubrication: rather than in the usual black ink, writers would put certain words in red such as the names of deities, rulers, or priests, religious incantations, beginnings of lines, or recurring set phrases helping readers follow the unfolding of the story. Rubrication created difference in a text and influenced the reading experience. It expressed reverence and an elevated status, but it also assisted the eyes and mind in navigating and processing. Rubrication has continued to be a feature of text ever since from medieval manuscripts to early printing in the Renaissance, and even today, hyperlinks are often blue, alerting us to a the highlighted word´s special status, pointing to something more, something outside this present text.

𓃠

Early punctuation was mostly a way of visually structuring text for improved cognitive understanding, but some hieroglyphic records attest to the first mark orchestrating voice. Some magic spells contain a pause sign which looked something like an extended arm with the fingers of the hand curled towards the elbow. This sign is an abbreviation of the word ‘grh’ meaning ‘to stop’, and was an indication for silence not to be said out loud in the same way that we don’t pronounce “colon”, we just pause.

Hieroglyphic writers probably did not have a notion of indicating pronunciation in genres other than spells where the act of speaking had agency, so the sound of that speech was crucial. Overall, ancient Egyptians faced issues that would become familiar questions to their punctuator-descendants in Greece, Rome, and further North: how to facilitate comprehension both by eye and ear, and how to speed up reading in the service of trade, administration, worship, politics, and culture.

𓃠

From Pictures to Letters

Over the course of another two thousand years, different kinds of writing systems like hieroglylphs contributed to the development of the alphabet, a game-changer for world history if ever there was one: the Phoenicians in modern-day Lebanon boiled down the hundreds of signs needed for expression in previous scripts to 22, exclusively referring to sound rather than syllables or whole words. These are the first letters. This change exploded the combinatory power of writing into infinity, allowing for flexible concise records of speech and thought. And writing has not changed fundamentally for 3000 years. Good ideas last!

As skilled naval traders, the Phoenicians carried their incredible brainchild all across the Mediterranean and beyond, becoming the basis for a huge number of global writing-systems from Hebrew and Arabic, to Cyrillic, and Latin. Around 800 BC, the Phoenician alphabet (classified as an “abjad” because it had no vowels yet) arrived in the Greek islands where vowels helpfully joined the hitherto consonant-only ranks of letters, rendering the distinction between words less context-specific (think of “st“ which could mean “sit“, “set“, and “set“). And that´s where we still are.

𓃠

And on a personal note: let´s hang onto writing a little longer. Let´s not replace it with videos just yet. It´s taken humanity so very long to develop an efficient expressive script, and the lack of change shows how very useful it´s been for just about any purpose a human being and a society could reasonably have in this life. One of my resolutions for 2025 is to read more, as in read more printed books. Although I am a writer, and was an academic for a long time before that, I admit that I´ve had enormous trouble focussing in the past years (besides reading for my work ). That´s surely a symptom of overall stress at world developments and my personal life, but it is also owing to scrolling, and feeling like I need to fill every silent minute with a podcast or other. It leaves me frazzled, and when I am just quietly going about my business cooking, or gardening, or walking the dog, I like it much better. The big quiet. The ease with which I manage to accept silence without anxiety-inducing mental chatter is a barometer of my internal peace that day.

As I am finishing my second book, I am noticing just how much mental and emotional effort goes into writing of this scale. It requires quite a prodigious effort of memory, vision, control, intuition honed by years of experience, and intimate knowledge of your subject matter, as well as self-trust, resilience, and stamina. And I am not saying that in a self-congratulatory way (lots of people have done those things before me), but more in an acknowledgement that a human-made book is infinitely more valuable than something a computer produces. It will always remain so. Writing a long book that´s both research-heavy and entertaining has given me a new appreciation of literature, and I mean the big L stuff.

I was reading (or attempting to read, seeing that I was so distracted) Jane Eyre in December. And I imagine Charlotte Bronte writing just like I was writing…on her own, by candle-light, thinking, thinking, and then some more, picking words carefully, sometimes, and sometimes more freely. And I felt such waves of connection that, somewhere in the North of England sometime in the late 1840s, there sat a woman, quill in hand. And here I am, writing, but more so: here I am, reading.

Because in the same way that writing the kind of book I do demands an enormous amount of intellectual ability and emotional involvement, it asks that of you, too. Reading it. This is absolutely a two-way street, and without you, there is no me, and the other way around. As a writer, I humbly beg for your patience, generosity, and trust in hanging around until I´ve slowly unfolded my points, hoping you´ll co-create this metaphorical meaning together with me. That´s an extraordinary relationship, actually. And a quite astonishing gift we give each other. Don´t let them fool you. ChatGPT can do a lot of things, but it cannot do that. That relationship.

And so, rather than to cram my head with meagre summaries of books, or with interviews with authors, I want to read read this year. I want to carve out 25 minutes a day at the very least that I put away the phone, and pick up a book with paper-pages. Because it connects me to you, and to Charlotte Bronte, and to phoenician traders, and Egyptian priests, and Sumerian scribes. Who would have thought that reading a novel peacefully on the couch is a radical act of resistance in 2025.