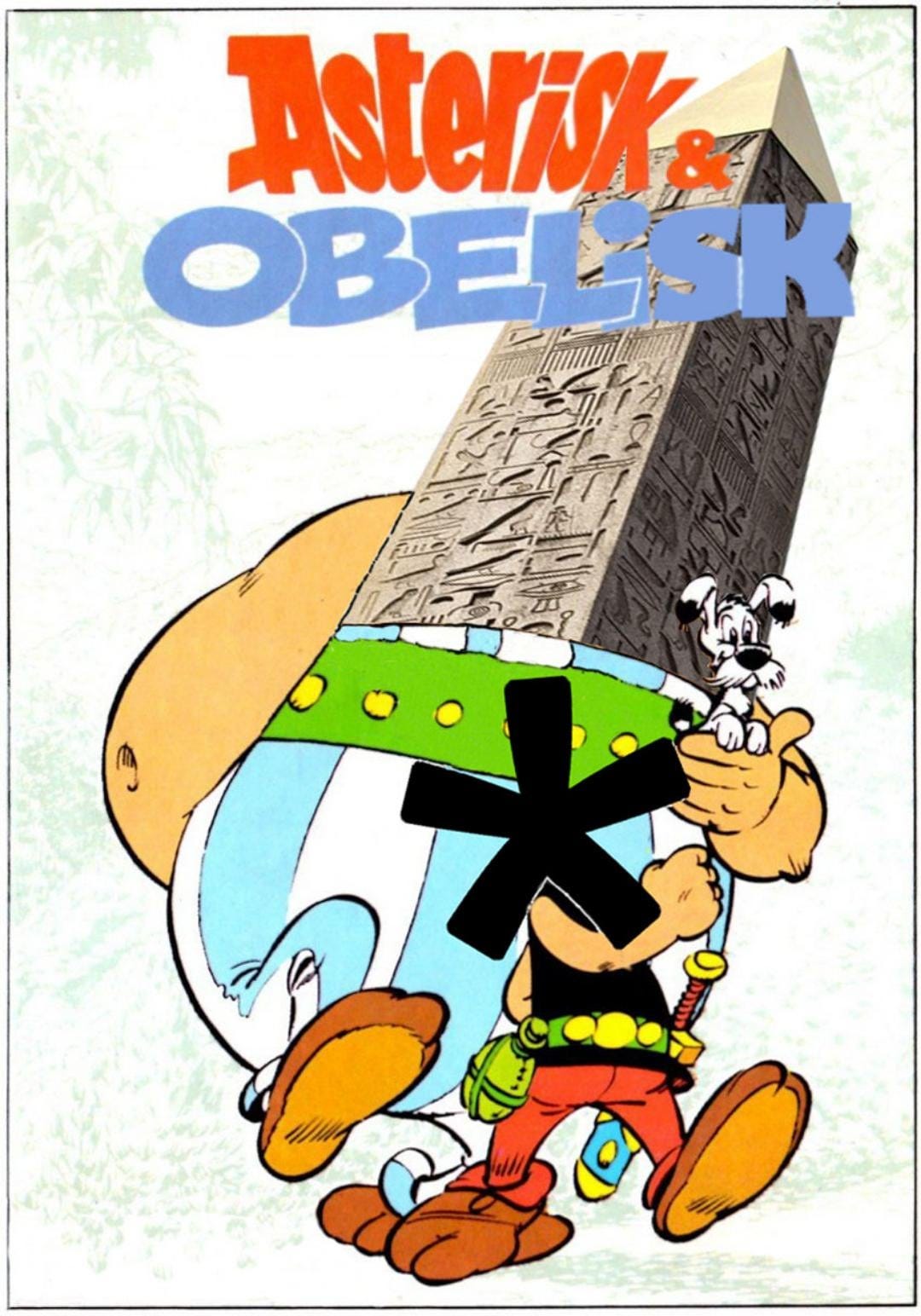

Can you guess the best-selling comic book the whole world around? Drumm roll, I mean Gallic war drum.…..exactly. Asterix and Obelix. From the inception of their French fathers René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo in 1959 to today, the adventures of the two unlikely friends have sold nearly 400 million comic albums, with almost 100 million sales of the comic that serialised their fights against Romans, British, Egyptians, and other ancient neighbours. What might the reasons be for this record-breaking success? The cute little doggo Idefix? The beautiful drawings, the fun adventures, the hilarious Gallic names? (To which I can attest, having lived in Geneva whose surrounding towns all ended on -ex!) Or maybe...it´s the comic´s punctuation!

Asterix (the short smart one) and Obelix (the strong chubby one) derive their names from the asterisk * and the obelos or dagger (÷ or † or ‡). Both punctuation marks are over 2000 years old, orginiating at the famed library in Alexandria where a succession of enlightened librarians kept inventing new marks to make reading easier. The asterisk and obelos helped navigate text, and establish an authoritative version of stories by signalling omission or duplicate lines (*) and flagging up faulty or spurious material (†) in the margins. Where there was an asterisk, an obelos wasn´t far. They were inseparable. just like our Gallic comic heroes.

Apart from the punctuation love between these two, the name choices also pay hommage to Goscinny´s grandfather who was a printer and typographer. Young Rene surely learnt all about textual signs and symbols beyond words and numbers in his grandfather´s print shop, and we must also not forget that drawing comics used to be a hand-made craft until not so long ago: artists started to produce digitally-made comics only from the 1990s onwards, although some made forays into eletronic tools earlier.

Drawing a comic meant pen and paper, and an intimate experience with the shape of letters, the vast array of signs we humans invented for writing, arranging picture and text on the page, and overall design. Asterisks, and obeloi (not sure about the plural here), exclamation points, and ampersands were the daily bread of a comic artist, and not just for character names or as appendices to BOOM! and POW! There´s swearing in comics, too, and plenty of it. Punctuation is its midwife.

Here´s what happens to punctuated-swearing in modern times. Spoiler alert: we´re much less adapt at taking the occasional fuck or two than Shakespeare or Chaucer were. Perhaps we can allow ourselves to follow their cheeky examples, some time or other?

Punctuated Growling: Naughty Comics

In punctuation-cleaned cussing Part 1, we explored replacing letters with asterisks, dashes, dots, or ampersands (&c. or etcetera) in order to sanitise, conceal, or playfully cover words perceived as rude like f**k or sh*t. Comics, however, omit even the words themselves, letting punctuation do all of the potty-mouthed work on their own, both representing and censoring four-letter-words. We don´t need to worry about which obscenity hides under the signs, because there´s no clue, and we can either supply it ourselves in thought, or simply understand that some swearing is going on.

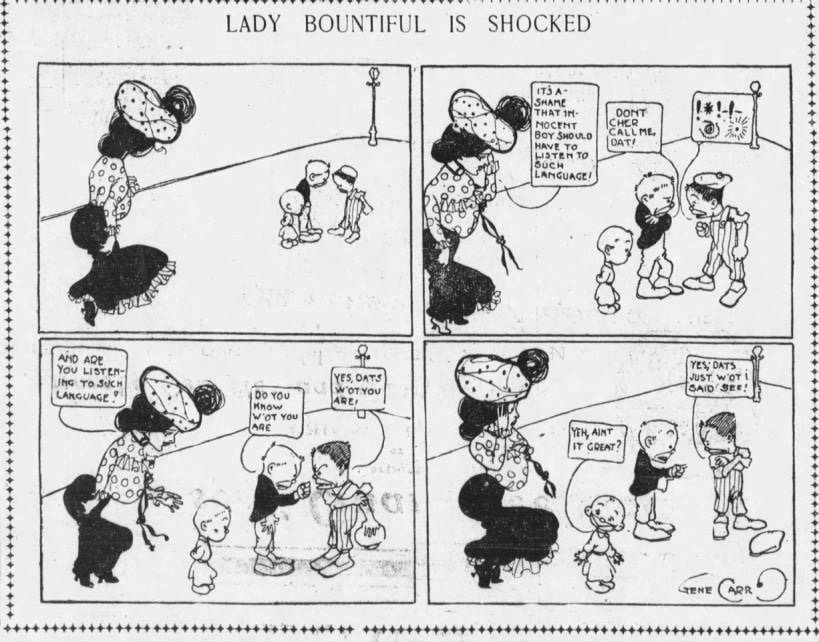

The practise started at the beginning of the twentieth century, probably introduced by Gene Carr in his Lady Bountiful, the first comic with a female protagonist, followed suit in 1902 by Rudolph Dirk´s Katzenjammer Kids. In his 1960s Lexicon of Comicana, Mort Walker calls punctuation-profanities “grawlixes” without telling us the idea behind the new word (perhaps from growling in a prolix, that is, protracted way). Comic fan Gwillim Law identifies original grawlixes containing spirals, planets, crescents, and anchors apart from punctuation. Sounds like early forms of emojis to me! When comic strips were no longer hand-drawn, artists focussed on keyboard- available characters like % and $ rather than little pictures.

¶

The X-Factor: Sonic Asterisks on the Wireless

How would you pronounce a grawlix? You can´t. The mechanism relies on us supplying any kind of expletives that we like, that we think the character would utter, or none at all, simply catching a feeling off the page. But the wish to swear remains. In the 1980s, a euphemistic contraction started to circulate which enables us verbally to refer to the naughty word without incriminating ourselves: x-words made the rounds. Speech researchers locate the first evidence in a satirical 1987 folk song by Lou and Peter Berryman called "A Chat with Your Mother" in which they warn "young people" not to use the F-word on a parental visit. Here´s the delightfully silly first stanza:

Oh, the pirates in their fetid galleons, daggers in their skivvies,

With infected tattooed fingers on a blunderbuss or two,

Signs of scurvy in their eyes and only mermaids on their minds,

It's from them I would expect to hear the F-word, not from you!

The F-word and its siblings like the C-word (cunt), or the N-word (nigger) are the spoken equivalents of asterisked profanity, making them acceptable on public radio or television. Should a reckless swearer drop the odd F-bomb after all, modern technology knows a remedy: bleeping. That old BLEEEEP, uniting the world in its universal piercing 1000 Herz, became necessary in the 1920s when the radio emerged as a new medium of communication -- and with that the uncertainty of accidental live swearing! 😱 Or not so accidental….

I´m so chuffed to tell you that BLEEP had to be instituted because of a woman! Yes, and a smashing kick-aBLEEP one, at that. Actress and women´s right activist Olga Petrova who was friends with the founder of the American Birth Control League, Margaret Sanger, went on air for an interview at a 1921 New Jersey radio station, sneaking in a seemingly innocuous nursery rhyme: “There was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children because she didn’t know what to do.” This veiled allusion to contraception was enough to have the radio crew scrambling to get her off the waves, because advertising for birth control was illegal, and could have cost the radio its licence. After this audacious act, sound engineers would have music at their fingertips to play over anyone foolish enough to pronounce such slippery slidey things.

After the founding of the American Federal Communications Commission in 1934, the fate of public swearing was sealed until today: when there´s something not-so-kosher being said, we hear the BLEEP, or a humorous dolphin cackle, plus a black bar over the mouth of the curser if it´s on camera, or asterisks, grawlixes, or [expletive]. Humans being humans, much mirth can be had by "incidentally" bleeping just that tiny nano-second too late, leaving too much of the word to function as disguise at all.

It is strange to realise just how very young the technologies are that we´re so used to, audio and video recording. It´s also strange (and frankly outright bizarre) how obsessed we seem to be with cleaning our language, or rather other people´s. For all our "modern" liberties, we´re not very free at all when it comes to speech. And I don´t mean hate-speech — I don´t believe anything goes — I mean natural expression.

¶

It´s always the Victorians.

We haven`t always been as anxious over written swearwords as we´ve explored in Part 1. So, what happened between now and Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Co.? In her preface to a new edition of her sister´s novel about wild and violent love Wuthering Heights (1850), Charlotte Bronte has little sympathy to spare for those flinching at coarseness: she connects unrefined language with the rugged moorland of Yorkshire, the cold and unforgiving home of those rough characters. It´s the symbiosis of language and landscape, and as such deserves being represented intact. Bronte believes it is "a rational plan to write words at full length", because the "practice of hinting by single letters those expletives with which profane and violent people are wont to garnish their discourse, strikes me as a proceeding which, however well meant, is weak and futile.”

It´s telling that Bronte´s renouncing comes when it does, in the middle of the nineteenth century. I don´t want to poopoo Victorians, and the period has certainly had to take way too much flak as instigators of contemporary sins concerning morality and authoritarian linguistic straightjackets — yes, women were either angels in the house or whores on the streets of London, but the lived reality looked different than our projections, and I´m sure there was plenty of fun and free stuff going on — yet, it´s undeniable that the standardisation of language in the service of the state, for one, was fuelled by social values hardening in the course of the nineteenth century. And that´s, amongst others, fixing spelling and punctuation, streamlining education, and creating bodies that oversee expression, telling us what´s the right thing to say (or write), and what not.

One manifestation of such expunging morality is what came to be known as "bowdlerising". Poor Thomas Bowdler, would he have persued his quest to tidy up Shakespeare had he known that his name was going to enter the Oxford English Dictionary as "castrating" words deemed offensive, now elliciting ridicule at such asterisk-hysteria? Perhaps he would still have done it! He might work for Meta today, cancelling certain posts…

In 1807, Bowdler published The Family Shakespeare, an edition of the bard´s works "unmixed with any thing that can raise a blush on the cheek of modesty" (preface). Considering that one of the innocent pastimes of decent families was reading Shakespeare out loud together, the tender ears of women and children needed to be protected. Without further ado, Bowdler thus cut around 10% of Shakespeare´s passages and words too-hot-to handle for the average nineteenth-century lady, for example Othello "tupping" Desdemona, or Ophelia´s suicide. The irony is that Bowdler´s sister Henrietta provided the first edition, but refused to publish it under her name, ashamed to admit that she understood Shakespeare´s salacious references.

Bowdler interprets the playwright´s willingness to insert "some things which ought to be wholly omitted" as a "compliance with the taste of the age in which he lived". Even a Shakespeare is not immune from stooping to “cheap laughter”, the damning conclusion goes.

Shakespeare´s (and Chaucer´s) etcetera is certainly about laughter, and there´s nothing wrong with that. More often than not, however, those very words and puns skirting around the edges of (our, not their) acceptability invite us to think about language, reading, theatrical performance, the workings of the mind. Past censorship was concerned with political edginess rather than a double entendre here and there. Shakespeare had his (co-written) play Thomas More scrapped by the censor because it had politically-explosive undertones. As far as we know, sexy stuff passed the axe, and trust me, some printed Renaissance poetry is 🥵🥵🥵! Manuscript works even more. (In the 1590s, Thomas Nashe wrote about a visit at his favourite prostitute for Valentine´s Day, involving a long description of a dildo. I mean!!!)

In his play The Constant Wife of 1927, Somersert Maugham wrote that we ´have long passed the Victorian Era when asterisks were followed after a certain interval by a baby´— but have we? In many ways, the climate is more repressive today than it has ever been. Here´s what I mean.

¶

Obscenity Obsessd — all this Filth nowadays!

In 2018, the mega retailer Target started to use asterisks in online book descriptions, scrubbing words it deemed problematic. The problem with this problematic-deeming was that regular words like "Nazi" (for a history book about the second world war) and "queer" (for a novel on queer love) fell victim to the axe of the censor.

If this wasn´t short-sighted enough, Target´s algorithm (or whoever was responsible for this misguided sanitising) wasn´t smart enough to understand the difference between "snatch" (slang for vagina) and "snatch" (a synonym for steal): Kell Andrew´s children´s book The Book Dragon who "snatch(es) books in the middle of the night" had its verb entirely expunged by little stars, giving the work a disreputably pornographic hint. The author commented: "I was embarrassed that my book was censored for vulgarity, and I thought the asterisks made the possible omission look even worse — as if the book might not be appropriate for children." Rather than simply returning all its words, "snatch" was swapped with "steal" which, according to Andrews, is neither the exact equivalent nor as evocative.

Simply replacing one word considered unacceptable with another considered inoffensive is certainly one way of avoiding the difficulty of addressing and assessing coarse language in writing. In 2012, Mark Twain scholar Alan Gribben has published a Huckleberry Finn edition that replaces "nigger" with "slave". Against a backlash of journalists, academics, and readers all over the world who saw this as white-washing the very same injustices Twain exposed, Georgia University Press justified its expurgation of what it considers the "disturbing racial label" thus:

"While dozens of other editions preserve the inflammatory slur that the author employed for the sake of realism, the New South Edition proves that the main point of Twain’s masterpiece—the immense harm deriving from inhumane social conformity—comes through just as vibrantly without obliging readers to confront hundreds of insulting racial pejoratives."

Thanks for treating us like babies with zero historical sensitivity to language change. Make no mistake, they´re not doing it for us readers. They´re doing it for themselves, for their own virtue signalling. This supposedly-cleaned edition of Huck Finn is much more harmful than asterisking a word, because it fiddles with the text sneakily. It covers up its traces, leaving us no way of knowing. Big Brother and the eternal over-writing of facts anyone?

In her highly readable For F*ck's Sake: Why Swearing Is Shocking, Rude, & Fun, researcher Dr Rebecca Roache gets up close and personal with "bad" words, unpicking the dynamics of textual bleeping. Considering the interplay of the rude word shining through its punctuation-cover like f**k or $h!t, she proposes that it´s not about de-fusing the word´s power to offend - that lies within the remit of the reader anyway - but about how "we manage to signal our solicitude towards our reader, yet we do so by substituting an offensive word with something that is barely less offensive." Asterisks, dashes, dots, blanks, black bars, and bleeps are supposed to communicate something about us, the writer: that we make an effort to anticipate the reader´s discomfort, and seek to protect them. Like emojis about which I wrote here, punctuation-concealing has a phatic function, that is, it doesn´t necessarily have much content or meaning, but rather it manages social relationships.

Whose feelings is the censoring writer really sparing, then? Theirs.

Whom are they patronising, claiming the right to assume offence taken or not? Us.

In an environment of cancelling anyone who refuses to follow superficial trends, spelling words out becomes a question of moral courage. Or something like that.

¶

Maybe...maybe we can do away with bleeping out certain words altogether, textual and otherwise. Scottish film maker Ken Loach put it astutely when he fought over censoring the seven instances of "cunt" in his movie The Angels´ Share: "The British middle class is obsessed by what they call bad language. [...] But the manipulative and deceitful language of politics they use themselves." It´s a similar issue to capitalising B/black on which I wrote here. It happens all-too-quickly that we get to hide behind spelling, stopping short of actual examination of social issues and activism. We police each other´s words, calling out and cancelling our peers, kicking sideways rather than up, against the system.

Ideally, language is a spring-board for debate, not a tool to clamp down on discussion, and feel good about ourselves. My work is all about the importance of nuance and detail, and how punctuation´s history is a deeply social one, intimately woven together with culture, with us humans; but perhaps, we don´t need textual bleeping, or perhaps only in official texts like the news but not literature. Perhaps we do need it. I´m not sure (yet). I find adjudicating between desire not to hurt and misplaced squeamishness difficult. The style guide of the Associate Press admonishes us that "vulgarity" needs a "compelling reason". Is being an essential part of every culture, every language, and every human life not compelling enough?

Perhaps, there is no one way of practising honest and caring writing. The core issue, as always, is to be discerning, and to choose consciously. To hand the choice over to readers. To consider them equal, and indeed crucial in co-creating meaning. People in the Middle Ages knew that. Shakespeare knew that. Why can´t we?

¶

P.S. During my research, I came across this incredibly catchy country song sung by Kevin Fowler, chastely expressing the…unpleasant…feeling of a hangover through #?*! — because of the children! 😂 Earworm material!

Just in case there might be

Little ears around

I won't say it

I'll just spell it out

I feel like pound-sign, question mark

Star, exclamation point

Don't give a blank

And a whole lot of other

Choice words I can't say

Today I feel like

Pound-sign…

P.P.S. I´ve deliberately not trigger-warned my full use of swearwords, and have deliberately not excised slurs, because exploring the history, practise, and logic of this is the point of the article, so the most neutral representation to me seemed to just write them out as Charlotte Bronte said. I´m in two minds about slurs, and can understand asterisking or x-word contracting them. On the other hand, I am not using them with an offensive intention, and it seems domewhat disingenuous to N-word when I ponder the self-congratulating motivations of punctuation-signalled textual queasiness. If I change my mind at some point, I will change the spelling, and make a note at the bottom like this one. Let me know what you think, I´m convincible!

F#%&@§ing great as usual ! Thanks for sharing Florence !